by Courtney Burns, Anna Morgan & Stephanie Terrell | Apr 22, 2021

Content warning: This post will contain discussions of sexual violence and misconduct. We recognize that readers of this post may have experienced sexual violence firsthand and/or have loved ones that are survivors. Supportive listening, help, and resources can be found at RAINN.

Our names are Anna, Courtney, and Stephanie, and we are the M1 leads for SafeMD, an organization founded in 2015 to promote an environment in which sexual assault is illuminated, understood, actively combated, and not tolerated. The three of us were deeply involved in sexual assault prevention and awareness prior to medical school and were eager to continue this work during our medical training.

SafeMD members presenting a poster at Health Professions Education day in 2018.

Anna spent her undergraduate years working with the Sexual Assault Prevention and Awareness Center at the University of Michigan and spent her gap year doing research on trauma-informed care. Courtney has an extensive history of engagement with activism to support survivors of sexual violence and spent her gap year working at a domestic violence shelter in rural Michigan. Stephanie has been involved with Title IX advocacy and survivor support and is currently studying applications of trauma-informed care.

Specifically, we are working to promote an environment in which survivors of sexual violence have access to and are aware of supportive resources in the medical community. We hope to provide future medical professionals with the necessary education to become proficient in caring for patients who have experienced trauma with nuance, skill, and empathy. To accomplish these goals, the founders of SafeMD in 2015 developed the initial projects of the organization: Allyhood Training and the Launch (M1 orientation) presentation.

SafeMD founder Seth Klapman presenting at the AAMC conference in 2016.

Since 2015, the role of SafeMD has evolved and expanded to fill identified gaps in the curriculum. For example, during this year’s M1 sequence on reproductive sciences, SafeMD invited a sexual health educator at the University of Michigan’s University Health Service (Laura McAndrew, MPH, PMP) to present on the origins and implications of sexually transmitted infection stigma, its impact on sexuality, and how to provide affirming care that increases treatment engagement and reduces inequities.

During February, Teen Dating Violence Awareness Month, SafeMD held a virtual journal club to raise awareness about the causes and consequences of adolescent dating violence. Additionally, because the M1 didactic session on intimate partner violence (IPV) in healthcare settings was asynchronous this year due to COVID-19, SafeMD hosted a live, interactive virtual session with the intimate partner violence (IPV) Doctoring content lead (Dr. Vijay Singh) to provide information on how healthcare providers can identify and respond to IPV.

SafeMD executive board members hosted a virtual journal club in February 2021 for Teen Dating Violence Awareness Month.

SafeMD has also developed a trauma-informed care workshop for medical students. Trauma-informed care in the healthcare field is an approach that assumes that a patient is more likely than not to have a history of trauma, and advocates for the promotion of a safe, transparent, and empowering patient-provider relationship. This interactive workshop, designed by current SafeMD executive board member Isabel Lott and former member Petrina LaFaire, was designed to provide medical students with an understanding of the principles of trauma-informed care and the importance of IPV screening, as well as give students a chance to gain confidence in effectively treating and communicating with a patient who has a history of IPV.

SafeMD Allyhood Training in 2017.

As SafeMD continually strives to maximize our impact on the Medical School community, we have incorporated self-analysis of training efficacy into the workshop by deploying a pre-post retrospective questionnaire to elicit feedback on the strengths and weaknesses of the intervention. We were able to analyze our data from Allyhood Training and present a poster at Health Professions Education Day. Furthermore, SafeMD also works with the Medical School’s Student Diversity Council to ensure that the curriculum is reflective of the fact that physicians across all fields of medicine will care for survivors of sexual violence during their careers.

April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month, and the SafeMD team has been busy! At the beginning of the month, we hosted a lunch talk from Dr. Tim Johnson, who discussed his work on the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine committee studying sexual harassment within academia. We also participated in Ann Arbor’s virtual Take Back the Night rally, and are providing free copies of Jennifer Hirsch and Shamus Khan’s book, Sexual Citizens, to medical students who would like to participate in a book club. Additionally, we are collecting messages of support for survivors of sexual violence throughout the month and will be organizing these into an art piece to be displayed long-term in Von Voigtlander Women’s Hospital.

April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month, and the SafeMD team has been busy! At the beginning of the month, we hosted a lunch talk from Dr. Tim Johnson, who discussed his work on the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine committee studying sexual harassment within academia. We also participated in Ann Arbor’s virtual Take Back the Night rally, and are providing free copies of Jennifer Hirsch and Shamus Khan’s book, Sexual Citizens, to medical students who would like to participate in a book club. Additionally, we are collecting messages of support for survivors of sexual violence throughout the month and will be organizing these into an art piece to be displayed long-term in Von Voigtlander Women’s Hospital.

If you’re interested in SafeMD, be sure to follow us on Twitter @UMichSafeMD and visit our website https://sites.google.com/umich.edu/safemd/!

by Gavisha Waidyaratne & Sangri Kim | Apr 8, 2021

What role do the arts play in medicine? When we first started medical school at the University of Michigan, neither of us could imagine that the arts would play a significant role during our four years here. We both came from undergraduate institutions with science-focused degrees, where art had been a hobby rather than an academic interest. However, over the last four years we have discovered a vibrant art and humanities scene that exists here at UMMS. Within it, we have found a community that seeks to bridge the gap between the arts and humanities and medicine. Now as we finish our last weeks of medical school, we can both agree that our exploration of this intersection has been a defining experience in our paths to becoming physicians.

At UMMS, we’re fortunate to have a robust Medical Arts Program that aims to help trainees provide more humanistic care through the study and reflection of the arts. This, and other programs like it in medical schools across the country are supported by increasing research that shows the benefits of art and the humanities in fostering important clinical skills. The Medical Arts Program at UMMS hosts a variety of extracurricular programs that include trips to local museums, musical performances, and opportunities for students to create their own art while reflecting on their experiences in healthcare. However, within the Medical Arts program, we thought there was space for more curricular medical humanities opportunities; this was the foundation behind our idea to create a formal elective experience for medical students at UMMS that similarly focuses on bridging the intersection between medicine and the arts: an elective called ‘Visual Arts in Medicine.’

Once this idea was born, we started with a needs assessment to look at the interest for a visual arts in medicine course amongst our peers. What we found was that many students felt that there was room for more curricular opportunities centered around the medical humanities. Once we knew a demand existed, we delved deeper into the literature and were excited to find that visual arts courses already existed at several medical schools across the country including Columbia, Harvard, Baylor, and more. Many of these courses focused on the connection between the visual arts and improving student’s objective observational skills used in clinical practice. However, when considering the breadth of our course, we decided that instead of covering one specific aspect of the medical arts in depth, we wanted our course to explore a broad number of ways in which art and medicine intersect. Our hope is to spotlight a wide variety of topics in this field and to spark an interest that may drive students to further embrace and explore the medical arts and humanities.

Our course is a two-week elective that will be piloted this month. It consists of 10 sessions, each focusing on a different aspect of art and the ways in which they can help us grow and develop as physicians. Sessions cover a wide range of topics from ‘graphic medicine’ and ‘art therapy’ to ‘plagues and pandemics in art’. Our course is sponsored by the Medical Arts Program, and we are supported by its incredible faculty leadership including Dr. Joel Howell and Dr. Lona Mody. Through designing this course, we have also been able to connect with an interdisciplinary group of individuals across the University of Michigan including art therapists, physicians, and graphic medicine artists, who do amazing work that intersects both medicine and the arts.

We have learned so much through this whole experience and are excited to see our course kick off. We consider ourselves very fortunate to have connected with such a rich medical arts community within the University of Michigan, and we hope that this course will allow other students to do the same. This whole process has been very empowering for us as students as well. When we decided to pursue this path in order to explore an area that we were passionate about, we were met with wholehearted support and encouragement. We found that as students here at UMMS, we have access to the resources and mentors we need to pursue or create new experiences that reflect our unique interests in medicine.

by Kayla Meyer & Cameron Pawlik | Apr 1, 2021

Imagine you are a 1st-year emergency medicine resident. Your attending is on call for the night shift you are working, and you are about to see your very first patient on your own. Before entering the room you read in the chart: 65 y/o cis-gendered woman presents with chief concern of chest pain that has been constant for 3 days.

You ask yourself, what could be going on? What should I prepare for before I see the patient? You quickly start to formulate your differential diagnosis, a list of possible diagnoses that could explain the patient’s chief concern and story.

An intimidating part of being a new medical student is figuring out how to come up with a differential diagnosis for the patient sitting in front of you. There are so many questions running through our minds as we learn more clinical skills and knowledge that it can be overwhelming to know where to begin with a patient presenting with shortness of breath, stomach pain, or chest pain. That is where the Chief Concern Course comes in!

An intimidating part of being a new medical student is figuring out how to come up with a differential diagnosis for the patient sitting in front of you. There are so many questions running through our minds as we learn more clinical skills and knowledge that it can be overwhelming to know where to begin with a patient presenting with shortness of breath, stomach pain, or chest pain. That is where the Chief Concern Course comes in!

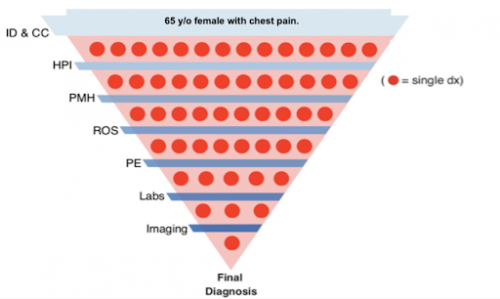

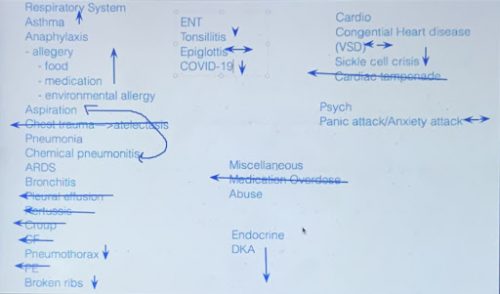

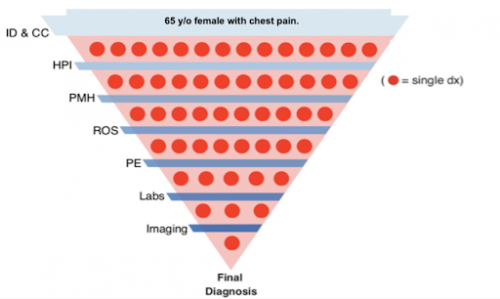

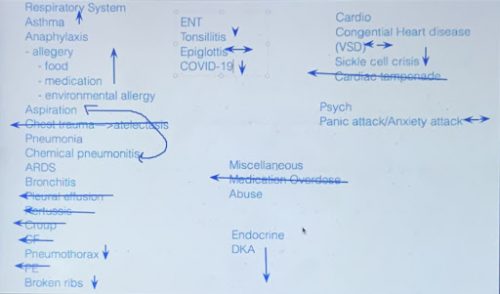

We are put in small groups of about 20 students and one faculty member physician and are provided a brief blurb about a patient. Before class, we are asked to come up with about 5 diagnoses, just like a doctor does before they see the patient. At the beginning of our virtual session, we all throw out any diagnoses we have based on the minimal information we were given in our prompt. This list is usually huge! We learned pretty quickly that some common presenting symptoms, like chest or abdominal pain, can be due to a variety of different systems — cardiovascular, pulmonary, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, or neurological to name a few! So without a lot of information, we have to start with a wide list. As we learn more about the patient and continue through the encounter, this list narrows. We start with asking questions and taking a patient medical history, performing a physical exam, and finally requesting labs and imaging. At the end of each session, with our monster list of diagnoses in hand, we are put into breakout rooms of smaller groups of 3-4 students to work on our next steps.

Back in the emergency department, you have developed your initial differential diagnosis, including gastrointestinal causes like cholecystitis or gastroesophageal reflux, cardiac causes like myocardial infarction or pulmonary embolism, pulmonary causes like pneumothorax, and musculoskeletal concerns like costochondritis. Now you are ready to enter the room to see the patient. What questions will you ask? What do you want to know more about? What will help you narrow down your list of diagnoses?

What additional information should we gather from the patient’s history?

In class, imagining we are about to interview the patient, we are placed into our smaller breakout rooms for our first objective: develop a list of questions to further gather information about the patient. A critical part about being a first-year medical student is learning how to take a thorough patient history. Thankfully, throughout our Doctoring sessions (Learn more about our Doctoring course here), we have learned how to inquire about the basic patient history, which includes information about their present illness, past medical, surgical, family and social history, medications, allergies, and a detailed review of systems. While this seems like a lot at first, surprisingly the more you practice the more it becomes second nature! What Chief Concern allows us to discuss, as a group, some of the key questions we’d like to ask the patient first. Because our medical knowledge is limited, this can be really tricky to narrow down relevant questions! We have really enjoyed working together with our classmates to come up with our plan for asking the patient’s history, especially because everyone remembers different key points from lectures and has different prior experiences and knowledge they bring to the group. This makes for great discussions and always serves as a great reminder that while we may think we know the exact questions that are relevant, often there are questions that would investigate diagnoses we hadn’t even considered.

After our first small breakout groups, we come back together to now ask our faculty lead the history questions we just generated, and they provide us the answers as if they were the patient. This is where we really start to think critically about which of our diagnoses are moving up on our list and which ones we can move down as being less likely. Some groups do this in real time by using the virtual whiteboard to start prioritizing a list! Here is an example of the resulting prioritization from one of our collaborative sessions:

What parts of the physical exam are we most interested in obtaining?

What parts of the physical exam are we most interested in obtaining?

Next, we get another opportunity to work with our breakout groups, but this time our goal is to discuss what we would be looking for in our physical exam of the patient. As we organize a list of what we’d prioritize in a physical, it helps to break it down into what pertinent positives and negatives we’d expect to find. For example, if we have a pneumothorax on our differential diagnosis for shortness of breath we would want to auscultate for absent breath sounds. If breath sounds are present that would be considered a pertinent negative for a pneumothorax.

When we return to the large group again, our faculty lead provides us with the full history and physical exam write-up. We now get to read through the most comprehensive information about our patient, and it is a great time to ask all our questions that we have about the presentation. Often, the patient case is not very clear cut or obvious, and there are multiple signs and symptoms that still fit with multiple diagnoses. This is where we now get to prepare our case (almost like a lawyer!) for what we think the top diagnoses are and what we plan to do about it, which is called the Assessment & Plan.

What imaging, labs, and/or interventions should we do to further diagnose or treat the patient?

In the emergency department or on an inpatient floor, as you are asking questions and gathering information, you will be mentally prioritizing the diagnoses, just as we did in class. In our experience in medical school, we are still honing our skills of balancing which diagnoses are most likely given the patient’s history with which diagnoses are life threatening and need to be managed urgently. This is where the assessment and plan comes into play!

The assessment is a list of just a few (about 3-5) diagnoses that are considered most important to focus on by the clinician, either because they are most likely or the most necessary to address. It includes a summary of the patient and important information discovered. Each of these diagnoses is listed with the factors that make them more likely and the factors that make them less likely. When we present our assessment to our attendings, they should be able to have a good idea of the patient’s story and key findings so far.

The plan is usually a bulleted list of interventions or diagnostic tools that creates a step-by-step guide for you or other providers to follow for the care of this patient. These tools are listed in order of what needs to be performed first and either grouped by specific symptom/problem or by organ system if the patient is in critical condition. These interventions could include things like IV fluids, medications, or even surgery. Diagnostic tools could be simple and quick like an EKG or complex and expensive like an MRI, depending on what is necessary.

After developing our assessment and plan, we come back to the large room and discuss our work as a group. It is a collaborative effort as we complement and critique each team’s work with input from both students and the faculty. It is a great opportunity to explore what it means to be a part of a healthcare team! After we each present, we are finally provided with the end to the clinical case. Our faculty runs through the results to any tests, labs, or imaging we ordered in our plans and unveils the final diagnosis. It is the end to a great full day of clinical reasoning, and we feel a little bit more prepared to reason through real patient stories in the coming years.

Put yourself back in the shoes of that first-year emergency medicine resident. Your history taking and physical exam has helped you discover the following:

History of Present Illness:

The patient’s chest pain is right-sided and radiates to her upper right shoulder and arm. She said it began 3 days ago after she ate a big helping of lasagna. She went to urgent care the next day and they gave her Pepcid AC, which didn’t help the pain at all. She then tried swallowing a baking soda mix, which also did not help the pain. She says it is really hard to get out of bed, because she can’t put weight on her right side. She denies any nausea, vomiting, shortness of breath, or lower leg swelling.

Past Medical History:

- Prediabetes x 4 years

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) x 10 years (has not had issues in years)

- Eczema x 3 years

Family History:

- Father: died @ age 65 of cirrhosis d/t previous alcohol use

- Mother: died @ age 78 of Myocardial Infarction (MI, a.k.a. heart attack)

- Older brother: died @ age 53 of venous thromboembolism (VTE)

Physical Exam/Vitals:

- BP 132/82, HR 75, RR 15

- No audible heart murmurs or irregularities

- Normal lung sounds

- Right upper quadrant (RUQ) tenderness to palpation

- Physical exam otherwise unremarkable

As an early practice, take this information (clinical story, given possible diagnoses, and reasoning strategies) and think about which diagnoses you would include in your assessment and do some research to find out what your next steps might be for this patient. Try to develop your own assessment and plan! We hope to see you alongside us in medical school and in the clinic in coming years where you can refine these skills!

by Victoria Stoffers | Mar 11, 2021

I grew up as a ballerina. Ballet was my life, my identity. When I discovered a passion for medicine, many people questioned how I could reconcile dual interests in both ballet and medicine- such seemingly different disciplines. However, since entering the field of medicine, I have developed a fondness for the differences between these two worlds, while also continually being struck by the parallels I find every day between the two.

Still enamored by both ballet and medicine, I have come to appreciate even more the opportunities I have had both in tutus and in scrubs, and further come to relish even more so the similarities I find across both. It seemed a natural step for me to join the Medical Humanities Path of Excellence at the University of Michigan Medical School, one of several interest-based pathways students have the opportunity to join. In the Medical Humanities Path of Excellence, I’ve connected with likeminded classmates and faculty also interested in the arts and the intersection of the humanities and medical sciences. For my Capstone for Impact, I wanted to create a lasting art exhibit that would allow me to share my experience and connect with others who may have similar experiences blending their worlds and passions across disciplines.

For my project, I dove into a new form of art for me – photography! This exhibit depicts my journey integrating my love for ballet and medicine. Through the process of staging and capturing these images, I came to realize even more similarities between dance and medicine than I had before. Trying to integrate such seemingly different objects and imagery, I was struck by both the tension and dichotomy as well as the harmony and blending of the two worlds. When ideas for certain images came to mind, I was surprised each time by how seamlessly the scenes came together. My two worlds blended together even more smoothly than I ever imagined, something I have experienced in my life over the past few years as well as through the journey of taking these photos.

The collection begins with still life images, consisting of objects typically associated with medicine strewn with subjects classically associated with ballet and the arts, creating a playful tension between the two while also showing how seamlessly they can appear to integrate. These first few images are meant to be subtle. The photos become increasingly more forward in demonstrating the melding of ballet and medicine as the collection progresses. Furthermore, the editing and lighting in addition to the subjects become more dramatic in each subsequent photo. This parallels my own feelings toward reconciling my passions for art and medicine. Initially, I tried to keep my worlds separate and not allude to one or the other my dual allegiances. However, as is demonstrated through the images, over time I have become bolder in demonstrating my passions for both dance and medicine, and finding ways to ensure both remain a part of my life.

This exhibit is meant to evoke the feeling behind my personal transition from one career to the next, from ballerina to doctor. My hope is that this collection will inspire others to give thought to ways in which seemingly dichotomous aspects of their lives may be more similar or harmonious than they once thought, and to find beauty in the contrast. I had a blast creating this project and was delighted by how well received it was by my peers and mentors. This is just one example of the incredibly unique opportunities allotted to University of Michigan med students.

Here is my photo collection – I hope you enjoy!

1. Tutus and S2’s

Early in medical school, our white coats and stethoscopes feel like a costume we don. These items feel like props from a child’s game of dress-up when we first put them on, but over time they become as much a part of us as a sign of our occupation. This photograph shows a stethoscope hanging amidst a wardrobe of ballet tutus and costumes. A tutu transforms the ballerina into a character for the audience and into a new version of herself for the performance. Similarly, the stethoscope is itself a symbol of medicine that transforms us from students into doctors.

2. Backstage

Putting on stage makeup and doing one’s hair becomes somewhat of a pre-show ritual for dancers. While execution of the choreography takes precedence for the audience, the hair and makeup are crucial to the performances well and also take time and dedication to perfect. Medical students spend countless hours training in physical exam maneuvers to prepare for seeing patients. While the reflex hammer may be an infrequently used tool amidst our equipment, it represents the tireless hours of preparation that go into evaluating, diagnosing, and treating each patient just as the makeup indicates the disciplined ritual of dancers preparing for each show with care.

3. E sharp

Music is an integral part of dance; it drives the movement and emotion of choreography. Here an eye chart is casually placed next to sheet music, accompanied by a tuning fork. This image is meant to evoke the playful dichotomy of the science of medicine next to the art of music, tied together by the tuning fork, which is used in both.

4. Simple. Interrupted.

This photograph shows a surgical needle driver and sutures being used to stitch a ballet shoe. This is meant to show a direct integration of the passion and skills of medicine and ballet complementing each other.

5. Breaking Scrub

The mayo tray with its surgical instruments is the surgeon’s toolbox. A ballerina’s pointe shoes are the primary tool she uses in her craft. This photograph displays a pair of pointe shoes among medical instruments and supplies on a surgical tray, exemplifying the contrast of the satin shoes amongst the cold metal instruments. While medicine, and surgery in particular, are often focused on as a hard science, they too are an art as physicians individually find solutions to the endless novel problems that patients present.

6. On Call

Here a dancer stands en pointe in a white coat, holding a stethoscope at her side. This image is meant to evoke a sense of both the tension and reconciliation of these two seemingly opposite worlds colliding.

7. Tipping Pointe

This final image is meant to be playful and thought provoking. I would like to leave this final image open to interpretation by each viewer. Perhaps one sees a dancer flippantly disregarding a stethoscope, abandoning science for art; perhaps one sees a physician skillfully balancing the stethoscope as well as her dual passions. To me, this image depicts the balancing act that we all undergo as we dedicate our lives to medicine and helping others, while also trying to remain well-rounded and continue to pursue our other passions, whatever they may be, that make us who we are.

by Yoni Siden | Feb 24, 2021

A few weekends ago, I, a medical student interested in ob/gyn and domestic health disparities, was the French representative to the (mock) United Nations at a summit on climate refugees. It was, in a word, unexpected. How had I found myself addressing the UN General Assembly? While the specifics of that January morning are still a bit confusing, it happened because this summer I decided to pursue a dual degree in Public Policy at the University of Michigan Ford School. A bit of an unexpected detour to my medical education.

Last spring, as COVID-19 descended on Ann Arbor, I witnessed the stories of this pandemic. On phone calls to tell patients about the transition to hybrid virtual prenatal care, pregnant patients told me of empty grocery stores, dissolving support networks, and job loss. As the pandemic worsened, it became clear that there was differential impact. Health disparities that had once felt abstract were suddenly in sharp focus and the medical community could not look away.

As a former social worker I am good at identifying problems, and as a medical student I am good at identifying the consequences of those problems. But I didn’t have the tools to address the issues these pregnant patients were facing: a disorganized food distribution network, loss of neighborhood cohesion, an economy in freefall. It was not news that these variables affect health, but what was less clear to me was what I could do about it. Carrying these patient stories, I decided to enroll at the Ford School of Public Policy because, as COVID-19 made clear, health starts outside the hospital.

Every day at Ford, we explore the biggest problems affecting our world. In fact, today alone I discussed optimal public insurance payment levels, affordable housing tax breaks, and privacy rights. I most appreciate the opportunity to go deep into complex problems. Some of my work has clearly been about health: I’ve explored the ethics of cost-benefit analysis of family planning programs, evaluated the ways trade policy affected the domestic supply of medical masks, and examined why the Affordable Care Act did not dissolve when the insurance mandate was nullified. But it isn’t health policy I’m interested in. The primary reason I came to Ford is to understand the scaffolding that supports my patients and shapes their lives. This year, I’ve written policy proposals for unemployment insurance, a campaign plan focused on childcare deserts (“no American family should need to make 1950s choices in a 21st century economy!”), and conducted an analysis of election day operations in Detroit. After all, more generous unemployment insurance keeps workers healthy, safe childcare helps stabilize families, and analyzing elections taught me about how complex systems, like hospitals, succeed and fail.

Complex problems require multi-tiered solutions, and while physicians and social workers are indispensable to any solution, so too are policymakers and community advocates who shape the communities our patients live in. The opportunity to pursue both ends of this continuum has been inspiring.

by Taania Girgla | Feb 18, 2021

My interest in the space sciences began in 5th grade when I read a biography on Robert Goddard (creator of the first liquid-fuel rocket). To say reading was a hobby would be an understatement because I could never be found without a book in my hands, but the stories I most enjoyed reading most were those that got me closer to space and the stars – stories such as biographies of Edwin Hubble, Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, or Sally Ride. As a child, I would fervently follow all NASA updates, mesmerizingly look at the night sky for hours, and watch all the space-related documentaries I could find.

Contributing to the advancement of the space frontier became my greatest childhood dream. To make this dream a reality, I always naively believed that I had to pursue a career in engineering. So, when I fell in love with biology and medicine at the end of high school, I thought my dream would remain just that. I did not know how to marry my love for medicine with my avid interest in space until I eventually learned of aerospace medicine (and its subset field of space medicine) whilst researching medical schools. Albeit a little late, I realized that I no longer wanted to delay pursuing my passion for space, and – as Professor Randy Pausch once said in his famous book The Last Lecture – I wanted to make my childhood dream a reality. Thus, when I was accepted to the University of Michigan Medical School in 2017, I committed to making a career for myself in space medicine and to bring it to my school and my peers.

Since then, I’ve immersed myself in the field and tried to soak up everything about it. I first attended the Red Risk School webinar series as an M1, which was how I learned of the Aerospace Medicine Association’s (AsMA) meeting the following month. I instantly spoke to my school counselor, Amy Tshirhart, to arrange for time off to attend the meeting. Amy knew of my interest in space medicine, and she has been my greatest advocate in pursing this interest during medical school – for which I will be eternally grateful! Attending that AsMA meeting in May 2018 was nothing short of a breath of fresh air for me. I felt rejuvenated and at awe at the world I stumbled upon where everyone shared the same passion for medicine and space as I did. I was shocked that I did not know about this community earlier, but I was committed to getting involved as soon as I could.

Since then, I’ve immersed myself in the field and tried to soak up everything about it. I first attended the Red Risk School webinar series as an M1, which was how I learned of the Aerospace Medicine Association’s (AsMA) meeting the following month. I instantly spoke to my school counselor, Amy Tshirhart, to arrange for time off to attend the meeting. Amy knew of my interest in space medicine, and she has been my greatest advocate in pursing this interest during medical school – for which I will be eternally grateful! Attending that AsMA meeting in May 2018 was nothing short of a breath of fresh air for me. I felt rejuvenated and at awe at the world I stumbled upon where everyone shared the same passion for medicine and space as I did. I was shocked that I did not know about this community earlier, but I was committed to getting involved as soon as I could.

Over the next few years of medical school, I slowly but surely began to reach out to faculty who could mentor me in this interest. It took me a while to collate a list of names – as this is quite a niche field – but everyone I spoke to was immensely supportive of my interest and supportive of helping me further develop it! This is what has been the best aspect of being at a school like the University of Michigan; instead of giving me a puzzling look when I said I am interested in space medicine, everyone at the school instead responded with curiosity, awe, and an equal eagerness to bring this unique topic to the school and share it with others.

With support from faculty and peer mentors (both at U-M and within the national aerospace medicine community I was now connected with) I applied to and have gotten accepted to NASA’s Aerospace Medicine Clerkship and the University of Texas Medical Branch’s Course in Principles of Aerospace Medicine – both of which I am scheduled to attend this year. Just earlier this week, I also submitted my application to a new medical student rotation at SpaceX! The opportunities for students are expanding, and I have been very excited about this!

Despite this rapid growth of space medicine though, to date, there are sparse formal educational opportunities available for medical students to gain more knowledge and exposure to the field. The few opportunities that do exist are found at select universities and are in-person experiences, thus limiting their accessibility. As a result, many students around the country, and here at UMMS, remain unaware of the application of and possibilities within the field of space medicine. This was how I became passionate about increasing students’ knowledge of and access to this field. Quickly, I realized that a short, online mode of delivery for this content does not currently exist, and this is the gap I hoped to fill. This led me to work on two projects that are quite near and dear to my heart.

First, I led the development of a two-week online and self-paced Introduction to Space Medicine elective for Branch medical students, which launched this January! The aim of this course is to create an online curriculum that informs students about the field and principles of space medicine. The goal is to inspire students to engage with and contribute to the ongoing efforts within the field of space medicine, to explore the possibilities of building a niche in this field for their future careers, and to become the next generation of leaders in space medicine. Through a series of readings, PowerPoints with integrated case studies, journal articles, online lectures/videos, podcasts, other supplementary assignments, and quizzes/assessments, students will gain insight into the field of space medicine, the effects of microgravity on human physiology, the health challenges associated with prolonged spaceflight and aviation, and current clinical applications to mitigate these risks. Through this course, students will also be introduced to the work of various leaders in the field of space medicine, and interested students can ask to be connected to these folks as career and research mentors.

This course has been well received by the 20 enrolled students thus far, and my next goal is to expand it to other schools at the University of Michigan and other medical schools nationwide. I developed this course with the help of a six-student team (across three different medical schools) and my faculty course director, Dr. Jim Bagin (ex-NASA astronaut and faculty in the Department of Anesthesiology). I owe a lot to my team to helping make this vision a reality! My partner in crime in this project, Riley Ferguson, has also arranged for this course to launch at her medical school (the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine) in January of 2022!

Second, I created a chapter for the Aerospace Medicine Student and Resident Organization (AMSRO) in the Fall of 2020 to serve as an interest group at the school, and I have been using the platform to help other interested students gain a footing in this field. I organize monthly talks and seminars which have drawn students from all over the world (UK, Russia, Saudi Arabia, India, Hong Kong, Malaysia, and Australia)! At the end of the day, I am most happy to cultivate students’ interests in this way and to promote connections and mentorships in this field for all.

Overall, though it certainly took me some time to find the space medicine community, now that I have, I am more eager than ever to dive in and contribute. I am humbled to see what has come of a vision I had early on in medical school, and I am excited to see what more will come of it! I know that with the support of the administration here, space medicine at UMMS will continue to grow and reach more students each year and expand nationwide!

Ultimately, my long-term goal is to combine my medical training and passion for space by contributing to the advancement of commercialized spaceflight one day. Achieving an enhanced understanding of this topic is of particular importance with the advent of commercialized spaceflight at the near horizon. As part of the next generation of physicians, I want to be ready for the responsibility to tackle the health challenges of this ultimate medical frontier, and I very much plan on making a niche in my future career for this work! I can only thank UMMS from the bottom of my heart for allowing me to pursue my passion for space medicine, helping me set my career trajectory in motion, and helping me get closer to making my childhood dream a reality.

April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month, and the SafeMD team has been busy! At the beginning of the month, we hosted a lunch talk from Dr. Tim Johnson, who discussed his work on the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine committee studying sexual harassment within academia. We also participated in Ann Arbor’s virtual Take Back the Night rally, and are providing free copies of Jennifer Hirsch and Shamus Khan’s book, Sexual Citizens, to medical students who would like to participate in a book club. Additionally, we are collecting messages of support for survivors of sexual violence throughout the month and will be organizing these into an art piece to be displayed long-term in Von Voigtlander Women’s Hospital.

April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month, and the SafeMD team has been busy! At the beginning of the month, we hosted a lunch talk from Dr. Tim Johnson, who discussed his work on the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine committee studying sexual harassment within academia. We also participated in Ann Arbor’s virtual Take Back the Night rally, and are providing free copies of Jennifer Hirsch and Shamus Khan’s book, Sexual Citizens, to medical students who would like to participate in a book club. Additionally, we are collecting messages of support for survivors of sexual violence throughout the month and will be organizing these into an art piece to be displayed long-term in Von Voigtlander Women’s Hospital.

An intimidating part of being a new medical student is figuring out how to come up with a differential diagnosis for the patient sitting in front of you. There are so many questions running through our minds as we learn more clinical skills and knowledge that it can be overwhelming to know where to begin with a patient presenting with shortness of breath, stomach pain, or chest pain. That is where the Chief Concern Course comes in!

An intimidating part of being a new medical student is figuring out how to come up with a differential diagnosis for the patient sitting in front of you. There are so many questions running through our minds as we learn more clinical skills and knowledge that it can be overwhelming to know where to begin with a patient presenting with shortness of breath, stomach pain, or chest pain. That is where the Chief Concern Course comes in!

What parts of the physical exam are we most interested in obtaining?

What parts of the physical exam are we most interested in obtaining?

Since then, I’ve immersed myself in the field and tried to soak up everything about it. I first attended the Red Risk School webinar series as an M1, which was how I learned of the

Since then, I’ve immersed myself in the field and tried to soak up everything about it. I first attended the Red Risk School webinar series as an M1, which was how I learned of the