by Emmanuel (Manny) Quaye | Aug 19, 2021

My research interests have evolved over the years. As an undergraduate at Michigan, I spent three months in Hangzhou, China studying iron deficiency and its effects on cognition in 9-and-18-month-old infants. Although I spent most of the summer coding videos and entering data, I learned much more about the process of conducting research, which involved lots of reading, asking questions, maintaining a healthy amount of skepticism, and most importantly, embracing the unknown.

Daniel Moura (on my right) and the entire research team alongside myself at the Zhejiang School of Medicine in Hangzhou, China.

After graduation, I spent one year working as an AmeriCorps Vista member, where I helped facilitate college access workshops for 9th graders and their families. As a Vista, I also had to live at the poverty level for Washtenaw County (the county Ann Arbor is located in), which was $13,000 at the time. Not only did I have to apply for food stamps and learn how to budget, among other life skills, but I also began to understand the financial hardship that many families in our country face on a day-to-day basis. Not knowing if you can afford rent, healthy food, or health insurance is something that many of us in medicine, including myself, don’t have to think about and often take for granted. This experience sparked my interest in health disparities research and led me to Johns Hopkins, where I earned a master’s degree in epidemiology.

As a graduate student, my research focused on the relationship between the social determinants of health (e.g., education level) and obesity using data from a community study called ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities). During my time in graduate school, my mentor Dr. Josef Coresh encouraged me to apply for a Diversity Supplement, a grant awarded to minority students to increase diversity in the research workforce. I learned in graduate school about the importance of choosing the right research mentor—someone who invests in your academic success and personal well-being, and connects you to others if there is a need they can’t meet. Typically, the process of finding the right mentor is often trial and error. I still remember the days when Dr. Coresh and I would go to spin class or eat dinner at Fells Point in Baltimore.

My mentor Dr. Josef Coresh (left), and I at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health graduation ceremony.

When deciding on where to attend medical school, I wanted to be at a place with excellent clinical training, ample opportunities for research, and a vibrant, diverse, and supportive community. Michigan fit all three criteria. I also knew that I wanted to get involved in research in medical school, but I was unsure about what kind of doctor I wanted to be and how to get involved. I reached out to an upperclassman I knew who had taken a year away from medical school to participate in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Medical Research Scholars Program. He loved his experience, and he and other mentors at Michigan encouraged me to apply.

The NIH Medical Research Scholars Program is a year-long, paid, mentored research fellowship on the NIH campus in Bethesda, Maryland. I chose to apply because the NIH is at the forefront of medical research. They have the world’s leading experts in every field of medicine, and all patients who receive care at the NIH Clinical Center (the nation’s largest research hospital) are on a research protocol. During the COVID-19 pandemic, being surrounded by the experts leading the charge to develop a safe and effective vaccine and other medical devices and therapies to combat the virus was truly a privilege.

My roommates and I enjoying some good food at our ugly sweater party.

At the NIH, I wanted to try something new and gain additional skills to complement my public health background. I also felt that to understand health disparities better, I needed to have a solid understanding of the biological determinants of health. At the NIH, I worked with Dr. Rebecca Brown, a fantastic mentor and world expert in lipodystrophy, studying the mechanisms of action of leptin therapy and associated changes in energy expenditure in patients with partial and generalized forms of lipodystrophy. The analyses I conducted led to new questions and hypotheses that turned into new projects.

Celebrating the groom Tochukwu Ndukwe (right), who is now a PGY-1 in Ophthalmology at the Illinois Eye and Ear Infirmary.

At the NIH, there were opportunities to take classes, attend national (virtual) meetings, listen to lectures by medical experts, and explore some of the great restaurants in D.C. My experience at the NIH was nothing short of transformative. I worked on exciting projects, formed new friendships with my co-scholars, learned from the brightest minds, and even had time to make it to my classmate’s wedding.

My journey in medicine has been filled with twists and turns, but each unique experience has helped shape me into the kind of physician I aspire to be. It’s okay to delve into new experiences even if it’s uncomfortable. Learning what you like and don’t like is critical early in your career, and having supportive mentors who have your best interest at heart can be life-changing.

by Rebecca Howland, Cassidy Merklen, and Netana Markovitz | Aug 11, 2021

As first-year medical students, we founded PalMD. It is a student organization dedicated to providing skills and knowledge to students on palliative and end-of-life care, regardless of desired specialty. We host lectures, interactive workshops, and events dedicated to wellness on the wards.

At our first PalMD event during our M1 year!

We each came to medical school with different reasons for our interest in palliative care. We had shadowed palliative care teams, conducted palliative care research, worked in hospice, and watched the suffering of family members eased by excellent palliative care teams. We had all seen the importance of clear, supportive communication in times of calm and crisis.

We were lucky to attend Michigan Medical School, where students are given every opportunity to pursue and explore passions, even by forming a new student group! So, as newly minted M1s, we put our heads (and passion!) together, and with the help of palliative care physician, Dr. Laura Taylor, formed PalMD.

Among our different types of events, our group hosts workshops to help empower students to cope with difficult encounters on and off the wards. Our recent event was a session focused on debriefing difficult conversations on the wards. The students at the meeting shared tough stories, and Dr. Taylor helped us work through these interactions. We left the session with clear heads and the tools to debrief future interactions.

by Kyle Wickham | Jul 22, 2021

From the moment I decided to apply to medical school, I knew that I was interested in working with underserved populations. As someone from a low-income background myself and from working with many underserved populations through volunteering and working in Chicago where I did undergrad, I saw the immense need for dedicated healthcare providers in these communities.

When interviewing at Michigan, I looked for the opportunities to work with these communities, as I did in all of my medical school interviews, and remember students discussing various ways they worked with diverse and underserved populations. From opportunities such as volunteering at the Student-Run Free Clinic or completing my emergency medicine rotation in Detroit during the Branches, I was excited about the various options Michigan gave to create a path in medical school that aligned with my passions. Despite this excitement, I was also worried that a core of my clinical learning, the clinical trunk or M2 year, would lack the opportunity to work with underserved populations as most of the clinical year is completed at the University of Michigan Hospital. While the University of Michigan sees patients from all over the state and even the country, it is no secret that a lot of patients in the Ann Arbor area are more affluent than surrounding cities and have access to excellent health care that not everyone in the country is afforded. I knew that I would receive a great education, but would I be able to help the underserved like I wanted to? It turns out the answer is yes.

M2s Kyle Wickham and Taylor Morgan at the orientation for the Hamilton Community Health Network rotation.

One of my first clinical clerkships was Family Medicine where I worked at the Ypsilanti Health Center. Ypsilanti is a town just southeast of Ann Arbor and is home to some of the best food I’ve found in the area (check out Lan City and La Torre, you won’t regret it). I chose this location not only for the food, but also to begin to see patients from populations I eventually wanted to work with in my career. During this month, I worked with patients who could not afford medication to control their diabetes, who didn’t want to go to the emergency room despite our suggestion due to the associated cost, who was in the process of getting deported and had to leave their entire family behind, and many others with circumstances and experiences that were novel to my medical career. I found that many of my appointments weren’t simply focused on diagnosing a condition and coming up with a plan to fix this medical problem, but rather having to discuss their life circumstances and put their health in the context of their overall life in order to come up with viable options that I might not have ever thought about with patients not in their position.

In addition to working in Ypsilanti, the Family Medicine clerkship also offers excursion days where you can work at various clinics or sites for a day to see different aspects of family medicine. These experiences ranged from doing home visits to working in a sports medicine clinic, but the one that interested me was the Corner Health Center, which is a clinic that provides free services to patients aged 12-25 that range from general health care, obstetric and newborn care, mental health, support services, and more. While I only spent one morning working at this clinic, I was excited to be able to participate in an organization that provided such necessary services and was working to improve the overall health of young people.

The last experience I had during my clinical year working with populations outside of Ann Arbor was during my outpatient month of Internal Medicine. During this month, students are typically assigned to specialty and general internal medicine clinics that they work at once a week; however, there is an option for students that are interested to request to work at a clinic that primarily works with underserved populations. As you can probably guess by now, I requested to work at one of these clinics and was assigned to Hamilton Community Health Network in Flint, MI. Hamilton Community Health Network is a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC), which means they receive money from the government to cover health care-associated costs for those who cannot pay and also see lots of patients with government insurance, such as Medicare and Medicaid. Their mission is to provide care for low-income patients, regardless of their insurance or ability to pay. In addition to general health care, the clinic I worked in included in- office dentistry, pharmacy, x-ray, blood labs, and subspecialty services from the University of Michigan such as urology and ob/gyn that saw patients weekly. Many of the patients I saw were unable to drive themselves or afford public transportation and needed to utilize transportation from their insurance to come to the office. With physical and/or financial restrictions, it was important for them to be able to see the doctor, get their labs, and pick up their prescription all in the same day at the same place or else they would not be able to. I saw how seemingly small things such as coming to a return appointment, which normally I would suggest to a patient without hesitation, were major barriers to the health care these patients received. This experience allowed me to see everything we take for granted in a well-resourced health care system and gave me experience working in an environment where all aspects of the patient’s life must be considered.

Reflecting on my clinical year, I am grateful for the opportunities I was given to work with populations that I care so much about. These experiences were among the most impactful I have had this year and have taught me important lessons that will make me a better doctor. While not everyone has the same experiences as me, I saw that you are able to tailor your clinical year to your interests and can see patients from different backgrounds than those at Michigan Medicine. As I enter the Branches, I am excited to continue to incorporate these experiences into my medical school career, and I have already scheduled a month to return to the Corner Health Center for an adolescent medicine rotation! While the Branches are a great place to explore your interests and passions, know that the clinical trunk has lots of flexibility and many unique opportunities to work with patients from many backgrounds.

by Lucy Zhuo | Jul 1, 2021

The trunks on most trees can look fairly similar. But the leaves on the branches can look quite different (like our curriculum)! Photo taken outside Taubman Health Sciences Library.

“Just wait until you get to the Branches!” I had heard some variation of this statement throughout my first two years of medical school whenever conversations about curricular flexibility came up. After finishing clerkship year and USMLE Step 1, my class entered into the “Branches” of the curriculum. As a brief primer, the University of Michigan Medical School divides the curriculum into two parts, the “Trunk” and the “Branches”. The Trunk is broken up into the pre-clinical and clinical trunks, which encompass the first two years of medical school at the University of Michigan. The Branches, the third and fourth years of medical school, is the 17-18-month period leading up to graduation that offers the freedom to explore future career choices and develop personal interests.

Admittedly, when I first heard about the Branches when I was as a pre-clinical “Trunk” student, the concept felt elusive, as our house counselors had told us that our experience would be what we chose to make of it. At baseline, we choose one of four possible Branch pathways, each offering a specific focus into patient care (Patients and Populations, Procedure-Based Care, Diagnostics and Therapeutics, or Systems and Hospital-Based Care) and establish relationships with advisors, both in our Branch and in our future specialty of choice (faculty career advisors). As part of our graduation requirements, we also must complete several rotations during the Branches, including at least four graded clinical electives, an ICU rotation, a sub-internship, and an EM rotation with protected time for residency interviews, a residency prep course, and vacation.

What I hadn’t realized as an M1 student was that as Branches students we would have a broad spectrum and diversity of opportunities at our fingertips, as long as we wanted to pursue them. We are encouraged to explore fields and interests that we may have a low likelihood of experiencing through residency that can help deepen previous interests or layer other interests to diversify and offer breadth to our personal studies. There are clinical electives from across 20+ departments — see a taste of what’s available below. Other more niche elective options include Wilderness Medicine, Comparative Medicine, Street Medicine, Disability Health, Visual Arts in Medicine, Medical Communication through Wikipedia, and more.

- Consult Service (Adult or Pediatric, 20+ services including cardiology, infectious diseases, and allergy)

- Anesthesia electives (Adult or Pediatric)

- Clinical Ethics Service

- Family Medicine in Japan

- Sleep Medicine

- Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Addiction Treatment Services

- Nuclear Medicine

- Interventional Radiology

- And…

The Branches offer significant time before working on residency applications to define and solidify future planning as well. For those who remain uncertain about their eventual field of choice, the Branches offer two week “exploratory” electives for students to learn more about fields that they hadn’t had previous exposure to, such as radiation oncology, dermatology, physical medicine and rehabilitation, anesthesiology, and sub-specialty surgical fields (orthopedics, ophthalmology, plastics, otolaryngology, neurosurgery, etc.). These electives are different from sub-internships (sub-Is), which are clinical rotations where the medical student is given the responsibilities and expectations to perform at the level of a first-year resident. A sub-I can be done on a variety of different services in a multitude of specialties.

There are many opportunities for creativity in the Branches as well. If a particular elective doesn’t exist, you can create your own individually arranged clinical elective (or INDARR as we affectionately call it). I have had peers create self-driven courses with topics such as cardiac electrophysiology, the intersection of transplant medicine and surgery, and narrative medicine (complete with a book reading list!). We can dedicate time and resources to work on research and our Capstone for Impact projects, our passion project intended to create a positive impact within health care. If there is a faculty physician we want to clinically learn from, we can arrange a longitudinal apprenticeship in which the student will go to the attending’s clinic on a weekly basis. During the months leading up to ERAS submission, some students will schedule clinical rotations at a different institution (“away rotations”) with the aim of experiencing a different institutional culture or eventually ending up there for residency.

As one example of the thousands of available permutations, my Branches schedule (listed below) has been focused on developing the perspective and skills to be a good general surgeon as well as revisiting my previous experience in health care finance and administration. However, this course I’ve charted for myself looks starkly different from my friend’s path (listed below mine), who is deciding between internal medicine and emergency medicine, with the final goal of critical care. If it’s not already obvious, some of the difficulty of broadly advising for the Branches is that your path forward is truly based on your own personal interests and future aspirations.

“Flight Paths” by Steve Waldeck, a 450-foot multisensory walk through a simulated Georgia forest, with a sculptural tree canopy that filters layers of light, surrounded by sounds and animation of local wildlife. Photo taken at Atlanta International Airport on my way home from Academic Surgical Congress (February, 2020).

My Branches path:

- Strategic Management for Physicians

- Anesthesia Clinical Elective

- Sub-I in Endocrine and Minimally Invasive Surgeries

- Surgical ICU Rotation

- Palliative Care Elective

- “Problem-Based Scientific Inquiry” (PBSI) Course

- Online Opioids Elective

- Research Elective

My friend’s Branches path:

- Anesthesia Clinical Elective

- Online Pediatric Injury Prevention Course

- Orthopedic Surgery Consult

- Medicine ICU rotation at St. Joe’s

- Emergency Medicine (EM) Rotation

- Sub-I in the IM Hospitalist Service

- EM away rotation at Henry Ford

- Apprenticeship with a pulmonary critical care physician

As my class enters the residency application season, the Branches have offered a wonderful period to prepare and propel us towards defining the careers we envision. We have the ability to draft the narrative we want as long as we’re willing to imagine it.

You can find more information about the Branches here.

by Anuj Patel & Hannah Glick | Jun 24, 2021

LGBTQIA+ people face a number of challenges in everyday life, including many health disparities. On average, LGBTQIA+ persons have higher rates of many chronic diseases and poor physical and mental health compared to cisgender and/or straight people. In addition, micro and macro aggressions when seeing a doctor are all too common for LGBTQIA+ people, whether that be in the form of non-inclusive intake forms or insensitive history taking or physical exams by physicians. When we started medical school as new M1s, and as members of the LGBTQIA+ community ourselves, we were acutely aware of this fact and were resolved to learn more about these health disparities from our patients and our curriculum, as well as seek and create methods to combat them.

Hannah Glick (left) and Anuj Patel (right) are leading the effort to create the first ever LGBTQIA+ Health elective at the University of Michigan Medical School.

In our M1 year, both of us were immensely grateful to have had the opportunity to serve on the leadership team for OutMD, our LGBTQIA+ medical student group at the University of Michigan. OutMD provided us a community of like-minded, queer medical students who were passionate about LGBTQIA+ health. Through our gatherings and monthly lunch talks, OutMD allowed us to learn about a number of topics in LGBTQIA+ health, including transgender hormonal care, LGBTQIA+ health policy, and primary care.

As medical students at the University of Michigan, we have a unique ability to incorporate our passions, like LGBTQIA+ health, into our education through curricular and extracurricular activities. However, while we were able to easily organize learning about these important topics extracurricularly, we felt that there was not nearly enough LGBTQIA+ health education embedded within our medical school curriculum.

As part of a collaboration with Dr. Dustin Nowaskie at IU School of Medicine and OutCare Health, we conducted a research project on LGBTQIA+ health medical education where we learned that medical students may need as many as 35 hours of curricular education in order to ensure high levels of LGBTQIA+ cultural humility in patient care. Michigan medical students were receiving far fewer hours than this benchmark. Driven by this gap, we aimed to create a new LGBTQIA+ Health elective for our medical curriculum as our Capstone For Impact project: a unique part of our curriculum which encourages students to reflect on their interests and passions, and to determine a project which results in a positive impact upon health, health care, and/or health systems.

In the Branches (as third- and fourth-year students) we are allotted ample flexibility to schedule a variety of clinical and non-clinical electives for in-person and online formats. Knowing this, we set a goal to create a new two-week, fully online Introduction to LGBTQIA+ Health elective for students to participate in during their third and fourth years. While creation of our curriculum is just getting underway, we have already received tons of support! We are lucky to be surrounded by brilliant faculty like our Capstone Advisor, Dr. Julie Blaszczak who is a member of the Family Medicine Department and an expert in LGBTQIA+ Health. She has been instrumental in supporting us to get this project off the ground. With the timeline we have in place, we are hoping to start offering this course to students in the Branches by 2022.

Our hope is that this new course will offer our fellow medical students a broad, comprehensive introduction to LGBTQIA+ health care. We plan to include a number of modules in our course that will cover basic background, language, and definitions, relevant history and policy, health disparities, clinical skills, and specialty topics in the care of LGBTQIA+ patients with input from faculty in primary care, psychiatry, pediatrics, Ob/Gyn, urology, plastic surgery, ENT, and dermatology. We plan to incorporate a number of different learning media including graphics, recorded presentations from content experts, news and research articles, and other existing resources.

We are incredibly excited and grateful to have the time and the support to incorporate our passion for LGBTQIA+ health into the curriculum at UMMS. We feel that this elective will leave an important and lasting impact on the UMMS curriculum and is a critical step in creating a new generation of LGBTQIA+ sensitive and competent physicians. Happy Pride!!

by Braden Engstrom | May 12, 2021

The show must go on.

I am told this cliché holds special weight for those who have spent significant time working in the theater, but I wouldn’t know. I was never a “theater person.” I had never acted, sung on stage, or produced any sort of production before coming to medical school. I never would have guessed that as an M4 I would find myself as one of the five people in charge of the massive production that is the Smoker.

The 2021 Smoker Czars standing in an empty Lydia Mendelssohn Theater looking super fancy.

The Smoker is an annual tradition and an integral part of the fabric of Michigan Medicine. For 103 years, students here have conceived, written, performed, directed, and produced this comedic musical. It is our way of satirizing the life of a medical student, reminding us all that those awkward encounters or difficult days are shared by us all. It is a chance to come together as a community, forget about studying, and share a laugh.

Additionally, the Smoker is how we show our love and gratitude for our educators. Faculty relish the opportunity to be “smoked” and regard it as the highest honor that students can bestow. As an M1, I fondly remember one of our most revered faculty appearing on stage dressed in a green morph suit and rainbow tutu, just days before he would welcome us to the neurology block. The support from the entire Michigan Medicine community (faculty, residents, students) fosters the idea that this place is not merely a hospital, but a family.

Neurologist Dr. Doug Gelb (far right) appearing onstage in the 100th Smoker “Harry Polyp” in 2018.

I found a home in the Smoker as an M1. I found best friends, faculty mentors, and lifelong memories. I knew I had to keep this tradition going and cultivate this same atmosphere for all. I spent the next two shows doing everything I could behind the scenes to help make the show happen, and as a fourth year I was named a Producer Czar (yes, the leaders of the show are arrogant enough to call themselves “czars”).

The cast of the 2020 Smoker, “The Nightmare Before Match Day” at the end of the show.

As I stood on stage for the final curtain call, I had no clue that in two weeks the University and world would be shut down due to the coronavirus. Everything I had ever hoped to bring to the stage was thrown into flux. For a few months, my fellow czars and I did what everyone else did: hoped things would blow over and we could go back to normal. Quickly that became unrealistic, and we knew we could not safely have an in-person musical. But, the show must go on. We knew that after one of the most tumultuous years in recent memory that we needed to give people a chance to laugh. It was then we decided to make the first ever The Smoker: The Movie.

The two Producer Czars for the 2021 Smoker sorting through the Room of Requirement that we refer to as the prop closet.

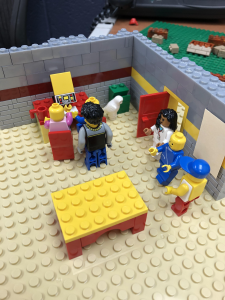

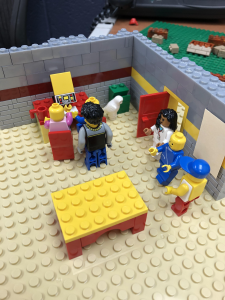

Making a musical as a medical student with limited theatrical experience is hard enough. Making a feature-length film with no movie making experience in the middle of a global pandemic is insane. Everyone filmed their own individual scenes, sang their individual parts, and danced their dances at home. I learned how to do LEGO stop motion and video editing for a scene in the show. In the end over 1,100 individual video files, 250 audio files, and 350 band tracks were submitted by students (who were still studying, on rotations, interviewing for residency, etc.) and stitched together into a full-length movie. Unlike a normal year when they can see the scenes come together in rehearsal and over Tech Week, the cast had as little insight into what the show would look like as the audience. Yet, they listened to our instructions and trusted our vision for a show–a fairly apt metaphor for medical training, too.

The behind the scenes process of making LEGO stop-motion animation for the 2021 Smoker.

This past Saturday, all of their hard work was realized, and we were finally able to release the 2021 Smoker, titled “Herpules.” I may be biased, but I think Herpules is as good as any other Smoker. Yet, I am proudest that the elements that made me fall in love with the Smoker survived. While the show will be memorable as the first movie version of the Smoker (and hopefully only), it should also be remembered as the year that despite every obstacle, the spirit of the Smoker lived on. Through all the virtual interactions, friendships were made, classes became closer together, faculty were smoked and made accessible to students, and, most importantly, the Smoker family grew. You can’t stop our team.

The Czars of the 2021 Smoker along with the new czars minutes before the release of Herpules.

The show went on. The show will always go on.

The 2021 Smoker, Herpules, is available to watch here. On this website you will also find a virtual program for the show, which contains even more history and insight into what the Smoker is about. Decades of past Smokers are also available to view on the Galens Smoker YouTube page.