by Caroline Richburg, Devon Cassidy, Brandon Ellsworth and Valeria S. M. Valbuena, MD, MSc | Apr 19, 2022

What is The LEAGUES Fellowship?

The LEAGUES (Leadership Exposure for the Advancement of Gender and Underrepresented Minority Equity in Surgery) Fellowship is a summer program in the Michigan Medicine Department of Surgery that is offered to medical students across the country between their first and second years of school. Our goals are to give early exposure to procedural specialties, and to create a pipeline for students who are from underrepresented backgrounds and who share our values of increasing diversity in medicine and surgery.

Each summer, LEAGUES fellows attend a four-week program at Michigan Medicine that includes seminars about surgery, sessions teaching key surgical skills, and mentored research projects with Department of Surgery faculty, culminating in a presentation at the Center for Healthcare Outcomes and Policy. The LEAGUES Fellowship was created by Michigan Medicine’s all-star general surgery resident Dr. Valeria Valbuena, and the program piloted in 2020. Our leadership team is made up of several UMMS medical students and surgery residents, and the wonderful Dr. Gifty Kwakye serves as our faculty advisor.

Getting Involved in LEAGUES

Getting Involved in LEAGUES

Caroline

Coming into medical school, surgery was not on my radar as a possibility for myself. I was an anthropology major in college, and I did not believe that I fit into the stereotypical box that I had in my head at that time for a surgeon. The summer after my first year of medical school, I participated in a summer program for M1s at Michigan called Surgery Olympics. In this program, I did social sciences research with an incredible surgeon who also happens to be a minority, an immigrant, a Black woman, and a mother. If Surgery Olympics was the ignition, my M2 rotation on surgery was the spark, and I fell in love with surgery. I wanted to find a way to combine my excitement for the field with my desire to pay it forward by building a more diverse and inclusive surgical workforce and mentorship group. And, as sometimes happens at the University of Michigan Medical School, into my email inbox “walked” Dr. Valbuena with LEAGUES and an opportunity to get involved.

What Makes The LEAGUES Fellowship Special

Brandon

To me, what makes LEAGUES a special program is its mission to help students who have fewer resources. Not only do we aim to recruit students from underrepresented backgrounds, we also intentionally look for students who may have fewer research or mentorship opportunities at their school. Additionally, the faculty mentors that we pair with students are excellent. They work with the students to develop a practical research project that fits their interests, and they continue to invest in the students once they return to medical school. Previous LEAGUES fellows have published peer-reviewed manuscripts with their faculty and used their faculty to build more connections throughout academic medicine. The Michigan Medicine Department of Surgery is passionate about the LEAGUES program, and their efforts have led to an unparalleled opportunity for medical students.

Built by Trainees, for Trainees

Devon

LEAGUES is a program built by and built for trainees. The unique aspect of peer-to-peer mentorship within LEAGUES has provided me with the opportunity to be a mentor, even as a student, and to learn from peers across the country. The LEAGUES Fellowship not only allows you to be a leader at every stage in medical school, but also emphasizes this role. During the LEAGUES summer lecture series I shared my experiences in health policy and advocacy and was able to later speak at a LEAGUES fellow’s medical school to inspire their student group to start a similar advocacy project. I also had the opportunity to attend an academic conference with one of our LEAGUES fellows, and as we both edited our presentations together, attended talks and networked, I saw the joy of peer learning and mentorship. I learned a lot from her experiences as a social worker and osteopathic medical student and continue to learn from our fellows. The LEAGUES Fellowship successfully recruits diverse medical students who enrich any environment they enter.

The Best Part of LEAGUES

Caroline

My favorite part of LEAGUES has been getting to know the people involved, including the fellows, my co-med student leaders, the residents and the faculty. Our LEAGUES fellows have been complete rock stars, and it is amazing to learn about the ways they live out their passions during medical school. It is also exciting to meet future colleagues in surgery from other medical schools. It is inspiring to get to know the residents who started and grew the fellowship and to see their example of allyship and advocacy during surgical residency. Listening to the program’s faculty-led seminars and learning about these leaders’ journeys to surgery has also been incredibly inspiring and motivating. Mentorship is huge, and our LEAGUES sessions leave me feeling inspired by leadership at all levels and encouraged about the future of surgery.

by Gabriela Kim | Mar 14, 2022

My first volunteer shift at the University of Michigan Student Run Free Clinic (UMSRFC) took place at the beginning of September. At that point I had only been in medical school for a couple months and had just begun learning basic clinical skills like how to take a patient history. While nervous at the thought of interviewing a real patient instead of an actor (we often have actors called Standardized Patients play the role of patients in class for practice), I was excited to try to apply what I’d learned in the Doctoring course to an actual patient experience.

I absolutely stumbled through my first couple patient encounters. I fumbled to find the right words, unsure of what follow-up and clarifying information to request when my medical knowledge was so limited. I performed a physical exam alongside a fourth-year medical student, who guided me through where to put my stethoscope and which parts of the patient’s chest I should listen to. When she asked me if I heard anything abnormal, I said no. Truthfully, though, I couldn’t hear anything. I only realized when I got home that I’d been using the wrong side of my stethoscope!

The U-M Student Run Free Clinic is located in Pinckney, MI and provides a variety of services including but not limited to basic primary and preventative care services, referrals to radiology or dermatology, and psychiatric and gynecologic services.

The UMSRFC is an organization that’s dedicated to providing quality health care at no charge to uninsured residents of Livingston, Washtenaw, and Oakland counties. It is run by a leadership team composed of students from the U-M Medical School, School of Nursing, School of Pharmacy, School of Social Work and School of Public Health. Throughout the pandemic, the clinic has been able to remain open and has continued servicing patients, with 635 total visits in 2021. [Learn more about supporting the UMSRFC at this link or below!]

Because of how insecure I felt about my own skills that first day at the clinic, I was really blown away by the other student volunteers. It seemed incredible to me that in three short years I would have the knowledge needed to ask the right questions, to confidently examine a patient and judge whether they needed further care. If anything, volunteering in the clinic really made me aware of how much I still didn’t know, and how much I would soon learn. That day I took my first patient history, I learned how to write up a patient visit, I presented an oral history to an attending physician for the first time, and I got just a brief insight into the incredible organization, dedication and effort that goes into running the clinic.

I also had the privilege of volunteering at the clinic on an “interprofessional education” day, so rather than just medical students volunteering, the clinic was also staffed by both nursing and social work students. Together, we were able to provide pretty complete services for patients who came in. Through phone translator services I could ask questions to a patient who only spoke Spanish, through the new dermatology e-consult service we were able to set up a patient for a specialist appointment to further examine an irregular mole, and, most surprising to me, we were even able to provide a diabetic patient with free insulin, which he could not afford himself.

Why the UMSRFC Matters to Me

I came into medical school knowing that I wanted to become involved with the UMSRFC. Throughout my entire admittance process, during interviews, Q&As with current students, and searches through existing organizations at the school, the UMSRFC constantly came up. Since you do not have to be a member of the leadership team to volunteer with the clinic, many students get involved with the SRFC to gain more practical pre-clinical experience taking histories and performing physical exams before starting rotations in the hospital during the second year of medical school. What’s nice about the clinic is that it provides a very low-stress environment in which students can practice the skills they’ve been learning. As nervous as I was during my first shift at the clinic, I was certain that the older students and the trained physicians volunteering would help guide me. No one made me feel dumb when I couldn’t remember what a medication did or didn’t know the correct “SOAP” format used when presenting to an attending; instead, they supported and guided me through the unfamiliar terminology.

Having the opportunity to participate in patient interactions so early on in medical school is certainly a compelling reason to join the clinic, but I was most drawn to the interpersonal aspect of work with the UMSRFC, the opportunity to become more involved in the greater Pinckney community that I would a part of for the next four years. This was driven by my personal interest in public health and desire to make connections within the community that could help inspire or influence any future pursuits in this area. And so, I applied for and was selected as the Community Outreach Coordinator for the UMSRFC.

As Community Outreach Coordinator, I’m primarily responsible for running social media pages, finding volunteer opportunities for medical students at community events where they can provide medical services and promote the clinic, and serving as a liaison between community organizations and the UMSRFC. I’ve met community members, organized events, and had the opportunity to learn to balance school and personal responsibilities with those of the clinic.

As students, we are also required to complete a Capstone project by the end of our fourth year. One way that many students choose to complete this requirement is by joining a Path of Excellence and completing their project under guided mentorship of physicians/professionals with similar interests. I recently joined the Ethics Path of Excellence and hope to draw from relationships and observations made through work with members of the greater community when developing my research project.

What’s really great about the clinic is that because it is student-run, there is a lot of space for creativity and the cultivation of new ideas. There is so much flexibility for people to begin personal projects aimed at improving the clinic and expanding access to care; the experience really becomes what you make of it. Because truly, the clinic could not run without the volunteer services of undergraduate students, graduate students, and various board-certified clinical providers. In 2021, the clinic was kept running by 3600+ volunteer hours in and out of the physical clinic space.

Support is Critical to the UMSRFC’s Success

While volunteers provide services in the clinic, we also really rely on institutional funding, grants and individual donations from generous supporters and donors to remain effective and to be able to continue improving our quality of care. Among other efforts, this year the social work team partnered with the Gleaners Community Food Bank to provide emergency food boxes to patients experiencing food insecurity, a dermatology e-consult service was started to increase access to highly critical specialized service, and we were able to increase the number of vaccines stored at and distributed at the clinic. The pandemic has also created new needs to keep both volunteers and patients safe, such as face masks, goggles, hand sanitizer and the expansion of our virtual services.

Giving BlueDay is a University-wide day of giving that encourages supporters to donate to the U-M programs that are meaningful to them, and donations collected during Giving Blue Day (and on any day of the year!) are crucial in allowing us to continue expanding our services. Last year, UMSRFC was fortunate enough to raise more than $20,000 to help expand our services and sustain the clinic mission.

I want to thank all past donors and invite individuals to share our Giving BlueDay page and keep the clinic in mind when considering what organizations to donate to this year!

by Taania Girgla | Feb 17, 2022

Contributing to the advancement of the space frontier has been my greatest childhood dream. Recently, I had the privilege and great fortune to make this dream come true – albeit just a little. Let me first give a little background:

Space medicine (a sub-specialty within Aerospace Medicine) concerns itself with the medical hazards of microgravity and prolonged spaceflight. There are two ways that one can really contribute to this field:

- Via an operational/clinical capacity where you are the one designing the medical protocols/recommendations for spaceflight; you are doing the pre-flight, in-flight and post-flight medical exams for astronauts; you are sitting at console in Mission Control monitoring the health of your astronauts; and etc. Last year, I had the opportunity to get very slightly exposed to this realm of space medicine while rotating with a commercial space company. Fortunately, we also have a UMMS alumna who does exactly this on a regular basis as a NASA Flight Surgeon!

- Via a research capacity where you are the one researching the effects of microgravity and prolonged spaceflight on physiology and health, investigating ways to mitigate the associated health risks, and developing countermeasures to the health hazards of the austere environment of outer space. Last year, I had the opportunity to get slight exposure to this realm of space medicine when I completed a rotation with NASA researching the microgravity-induced blood flow anomalies within the jugular veins.

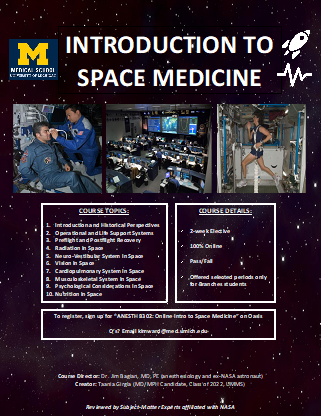

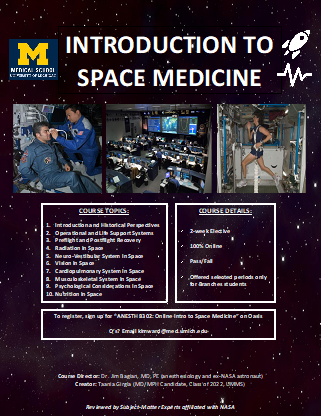

Space Medicine Elective at Michigan

I genuinely believe that I was fortunate enough to be chosen for these experiences because of the work I previously did to create a Space Medicine Elective at the University of Michigan Medical School (UMMS). UMMS always strongly and proudly supports its students’ unique curiosities, and I will forever be grateful to the school for this! When I spoke about my interest in space medicine with my counselor, the administration and faculty mentors alike, I received so much support from everyone to bring my vision of a medical school Space Medicine Elective to reality. It took hard work and time, but last year the course was formalized as an official part of the course catalog (housed within the Anesthesiology Department), and it has since also launched at the University of Cincinnati’s medical school! I have so many people to thank for this – ranging from the student team that helped me build the curriculum, to the subject-matter experts who vetted the content, to Dr. Bagian for offering his expertise as course director, to mentors within the administration and Anesthesiology department who helped make the course come alive, and to my counselor who first sparked life into the idea.

I genuinely believe that I was fortunate enough to be chosen for these experiences because of the work I previously did to create a Space Medicine Elective at the University of Michigan Medical School (UMMS). UMMS always strongly and proudly supports its students’ unique curiosities, and I will forever be grateful to the school for this! When I spoke about my interest in space medicine with my counselor, the administration and faculty mentors alike, I received so much support from everyone to bring my vision of a medical school Space Medicine Elective to reality. It took hard work and time, but last year the course was formalized as an official part of the course catalog (housed within the Anesthesiology Department), and it has since also launched at the University of Cincinnati’s medical school! I have so many people to thank for this – ranging from the student team that helped me build the curriculum, to the subject-matter experts who vetted the content, to Dr. Bagian for offering his expertise as course director, to mentors within the administration and Anesthesiology department who helped make the course come alive, and to my counselor who first sparked life into the idea.

I hope for everyone who reads this blog to enroll in the 2-week elective if you get a chance! The curriculum involves a series of readings, PowerPoints with integrated case studies, journal articles, online lectures/videos, podcasts, quizzes, assessments and peer student presentations. Through these, students gain insight into the field of space medicine, the effects of microgravity on human physiology, the health challenges associated with prolonged spaceflight and aviation, and current clinical applications to mitigate these risks. I know that with the support of the administration here, space medicine at UMMS will continue to grow and reach more students each year and expand nationwide! For those at other schools, we would love to work with you to help model something similar at your institution if you are interested, so do not hesitate to reach out!

Ultimately, my long-term career goal is to combine my medical training and passion for space by contributing to the advancement of commercialized spaceflight one day. Many folks ask me which of the two above ways I hope to contribute to space medicine, and my genuine answer to this is that I am not quite sure yet. What I do know with full certainty is that I am of no use to the space medicine community unless I am a competent physician first, so my first priority is to focus on my clinical training during residency. But eventually, as part of the next generation of physicians, I want to be ready for the responsibility to tackle the health challenges of this ultimate medical frontier, and I very much plan on making a niche in my future career for this work!

Overall, I can only thank UMMS from the bottom of my heart for allowing me to pursue my passion for space medicine, helping me set my career trajectory in motion, and helping me get closer to making my childhood dream a reality – and I want to help pay this forward to others. If you share this interest and/or are curious about the field but do not know how to get started, please reach out to me, and I would be more than happy to talk through it with you.

Advice for Gaining Exposure to Space Medicine

- If you have the means, go to the annual Aerospace Medicine Association’s (AsMA) Conference. Everyone everywhere in the world who is doing anything space medicine-related meets at this conference, so seek out this opportunity to network and get your foot in the door. This is also THE place to learn more about the field and assess for yourself if it is something you are energized by and if you can envision a niche for it in your future career.

- Become a dues-paying member of AsMA and AMSRO (which stands for Aerospace Medicine Student and Resident Organization – a constituent of AsMA). This gets you on their listserv, and thus gets you plugged into the community and opportunities within it.

- Apply for the scholarships offered by AsMA and AMSRO. Many of these are targeted towards students who are just starting to gain exposure to the field, so it’s a great opportunity!

- Take the initiative to educate yourself about the field at your own time! There are plenty of online lecture (like the Red Risk School Series and the Baylor Space Medicine Lecture Series). Take the Intro to Space Medicine elective as a Branches student to learn even more!

- If you have a local AMSRO chapter, join it!

- Take the initiative to reach out to and connect with students around the country who share this passion! It is a very niche field and a small community that is vastly spread out over the country. You may be the only one with an interest in space medicine in your immediate proximity, but I guarantee you that there are others who share this interest and who are probably doing work in it already too.

Many folks ask me which specialty they need to choose to get involved with space medicine in the future, and here I will share the advice I once received: it is likely that any number of days you spend being a “space doctor” is going to be less than the number of days you spend being a “doctor doctor”, so choose whichever specialty you genuinely enjoy and then find a way to make it relevant to space medicine. Throughout medical school, I was drawn to Anesthesiology and Ophthalmology – both fields that are not heavily represented in space medicine. In fact, the most heavily represented fields in the space medicine are Emergency Medicine, Internal Medicine and Family Medicine, but do I also know a Plastic Surgeon in space medicine? Yes. Do I know a Radiologist in space medicine? Yes. Do I know a Urologist and Orthopedic Surgeon in space medicine? Yes. You get the point.

With the advent of commercialized spaceflight upon us, the “typical” person now has the chance to go to space, and with that comes a whole set of new medical challenges that will need to draw upon the skills of various medical specialties – so my advice to others now is also to do what you love and make yourself relevant!

GO BLUE!

by Courtney Burns | Jan 6, 2022

Before medical school, I worked as a crisis counselor at a domestic violence shelter in rural Michigan. I saw the lasting effects of trauma and its manifestations on health, and quickly realized my passion within medicine: trauma-informed care (TIC).

TIC is a framework of medical practice that promotes autonomy, safety, empowerment and healing, and that recognizes individuals are more likely than not to have experienced at least one traumatic event during their lifetime (to be exact, research shows 89% of U.S. adults have been exposed to trauma). TIC is essential for clinicians because trauma has been documented to have deleterious impacts on health; these events can lead to difficulty accessing medical care, remaining engaged in treatment plans, and feeling psychological safety when receiving care.

At the Duderstadt Center on U-M’s engineering campus advocating for survivors of sexual violence.

Despite this, education on TIC in medical schools across the U.S. is largely absent, and upon starting my M1 year at UMMS, I quickly realized that our first-year clinical skills course did not include any instruction on TIC. However, a special characteristic about UMMS is how receptive the faculty and staff are to curricular improvement, especially regarding strengthening social justice and humanism as key pillars. The clinical skills course leadership immediately responded positively to my advocacy for inclusion of TIC in the curriculum, and asked me to use my prior work and research experience on trauma and TIC to design, implement and evaluate an evidence-based TIC workshop to be completed by all M1s in the fall of 2021. Excited to dive into this medical education project, I enrolled in the Scholarship of Learning and Teaching (SoLT) Path of Excellence program, which allowed me to engage in structured medical education training on a regular basis during my M1 year.

The culture of mentorship at UMMS is second to none, and I had the pleasure of working on my project with the close mentorship of Dr. Lauren Owens, a faculty member in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. In forming this team, known as Michigan Trauma-Informed Care Education (M-TIME), I also partnered with my incredible classmates Luca Borah, Stephanie Terrell and Elizabeth Erkkinen, each of whom has work experience in trauma-informed care as well. The foundation of our project involved working with LaTeesa James, a health sciences informationist at UMMS’s Taubman Health Sciences Library, to conduct a formal scoping review of the empirical literature on TIC curricula in the health professions. Sifting through more than 1800 articles, we identified the 51 articles meeting review inclusion criteria and quickly got to work synthesizing the strengths of these programs for use in the UMMS TIC workshop.

To support myself financially during the summer between M1 and M2 as I completed this project, I applied for and was awarded the $1,000 M1 Summer Impact Accelerator grant through the medical school. I also knew that part of my project would be designing a retrospective pre-post survey instrument to capture comprehensive data about the workshop’s efficacy and collect narrative feedback from the M1 students about areas for improvement. To maximize survey response rate, I was awarded a $2,000 Capstone for Impact grant through the medical school; this enabled me to provide a $10 gift card to a beloved local coffee shop, Sweetwaters Coffee and Tea, to every single M1 student who completed the survey after the TIC workshop. In implementing a participant survey, I also wrote and submitted an application to the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB), the first of many IRB applications to come in my career.

At the Nobel Peace Center in Oslo, Norway after giving a podium presentation at the European Conference on Domestic Violence.

The TIC workshop took place in October 2021 and was a huge success! The workshop components included: (1) a didactics portion emphasizing the link between trauma and health outcomes, best practices for trauma screening within patient encounters, and physician vicarious trauma; (2) a case-based session to practice TIC skills in small groups; and (3) a structured debrief. For statistical analysis of my survey instrument data, I partnered with a statistician at RISE (Research, Innovation, Education, Scholarship), a hub for medical education innovation at Michigan Medicine. I am so happy to share that 129 out of 170 M1 students completed the survey (75.9% response rate) and that our analysis illustrated statistically significant (p < 0.001) increases in students’ knowledge of TIC, intention to integrate TIC into their future clinical practice, and confidence in TIC skills. Moreover, narrative survey responses showed an overwhelming desire for increased curricular time devoted to TIC in the future.

Now that the workshop has concluded, I have shifted my attention toward disseminating the results of this project and am beginning to conceptualize improvements to the TIC curriculum for next year’s entering class. With mentorship from Dr. Owens, I have written several first-author publications about this work, and have greatly enjoyed connecting with trainees and physicians around the country who also study TIC in medical education.

With my medical school partner in crime, classmate Jacqueline Lewy, who provided the most amazing support and sounding board as I completed my project.

The success of designing, implementing and evaluating an evidence-based curricular intervention for 170 first-year medical students relied upon the unique constellation of resources and support available to UMMS students, including: (1) the SoLT Path of Excellence and steady stream of individualized advice from enthusiastic Path advisors Drs. John Burkhardt, Dan Cronin, and Caren Stalburg; (2) LaTeesa James, a health sciences informationist at the Taubman Health Sciences Library; (3) the $1,000 provided by the M1 Summer Impact Accelerator and $2,000 provided by the Capstone for Impact grant; (4) the statisticians at RISE; (5) the mentorship by faculty member Dr. Owens; (6) the assistance of my classmates Luca Borah, Stephanie Terrell, and Elizabeth Erkkinen; and (7) the enthusiasm of the first-year clinical skills course staff for curricular innovation and improvement.

All of this is to say that at the University of Michigan Medical School, if you can dream it, you can do it. The faculty and staff here at UMMS enthusiastically champion student projects — my TIC curricular intervention is a true testament to that.

by Kate Panzer | Jan 6, 2022

As I walked down the hallway of the University of Michigan hospital, a simple sign caught my eye. Taped to a patient’s door, the sign declared, “Patient uses American Sign Language (ASL)” in bold black letters. I entered the room, smiled and waved to the patient. His eyes met mine and quickly flickered away, as if I were there to speak with his daughter instead. His daughter explained he was deaf and did not communicate in spoken English. I turned to him, introduced myself and asked how he was doing. My hands and facial expressions flowed in synchrony to convey my intended emotions of interest and empathy.

His eyes lit up in surprise as he recognized ASL. His arms and upper body sprang to life, clearly forming his hands and facial expressions to describe every detail leading up to his hospitalization. Our connection was instantaneous, bound by a language and a mutual appreciation for its community, culture and pride. He taught me that a simple conversation in a patient’s primary language can create a unique bond — a form of healing that extends beyond medical treatment.

My own ASL journey began fortuitously during my sophomore year at the University of Pennsylvania. I enrolled in my first ASL class to fulfill a social science requirement for my bioengineering degree. Little did I know, that first class would inspire me to take four semesters of ASL and pursue a lifelong mission to improve access to healthcare for people with disabilities.

Upon graduating from college, my budding interest in Deaf Health led me straight to Michigan Medicine — home to the Deaf Health Clinic. As a clinical research assistant, I worked closely with Drs. Michael McKee and Philip Zazove, both ASL-fluent physicians in the Family Medicine Department who established the Deaf Health Clinic. Through this work, McKee and Zazove became my mentors and support system as I explored the field of disability health.

With this new exposure to disability in medicine, I sought out disability-friendly institutions when applying to medical school. Fortunately, the University of Michigan Medical School (UMMS) had clearly shown its commitment to disability. From the learning specialist and mental health services to the faculty support from the Center for Disability Health and Wellness, UMMS offered many opportunities to further explore my interests in disability and Deaf health.

As a newly minted medical student, I recognized the need to expand disability inclusion in medical education. Very few medical schools prepare students to partner with Deaf patients, resulting in barriers to communication and adherence. Inspired by the life-changing impact of my ASL classes, I hoped to provide a similar experience for other medical students and increase the number of Deaf-friendly physicians. Thus, in January 2021, I began working with a diverse team of students, faculty and interpreters to establish an ASL elective for medical students.

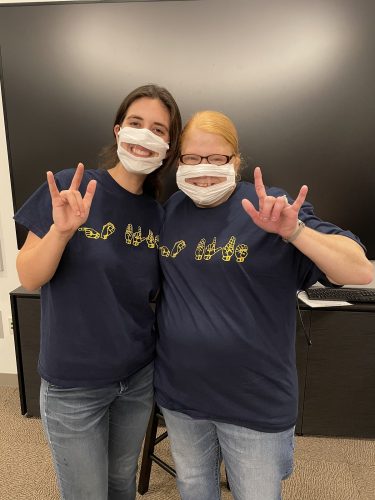

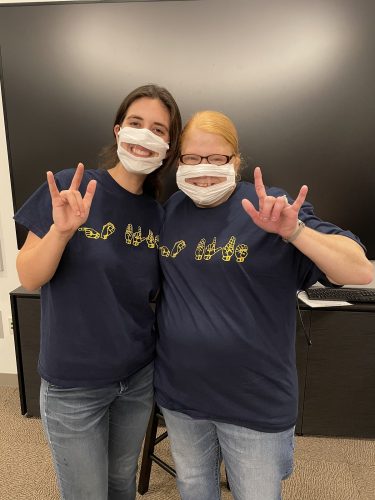

Kate Panzer (left) and Professor Shields (right) show off their “GO BLUE” shirts at the final ASL class.

To start the process, we needed all hands on deck. Our team began brainstorming ideas, emailing school administrators and searching for funding sources. I sought advice from student leaders of the medical Mandarin and Spanish electives and pitched the course to a Zoom room filled with faculty. By June, the course was officially approved, allowing us to share the instructor job description on various social media platforms. After reviewing several resumes and interviewing applicants, we were fortunate to hire Professor Julia Shields — a Kalamazoo resident, experienced ASL instructor and member of the Deaf community.

The summer break proved to be an ideal time to prepare for the elective. I spent many hours working with Professor Shields on curriculum development and recruitment materials. After first-year medical students settled into the school year, I distributed information about the elective along with an interest form. With such a new elective, I was uncertain about the level of commitment we would receive. Thus, I was moved by the 44 students who completed the form, nearly one quarter of the first-year class! Although that number declined due to other passions and limited time, 22 enthusiastic medical students officially enrolled.

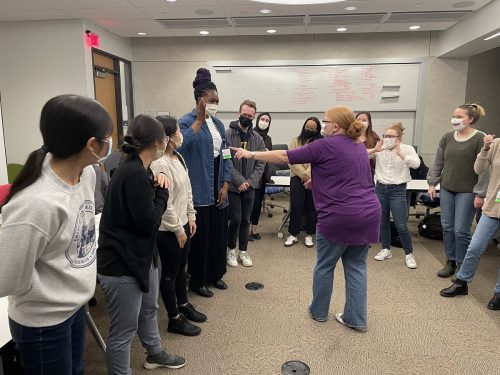

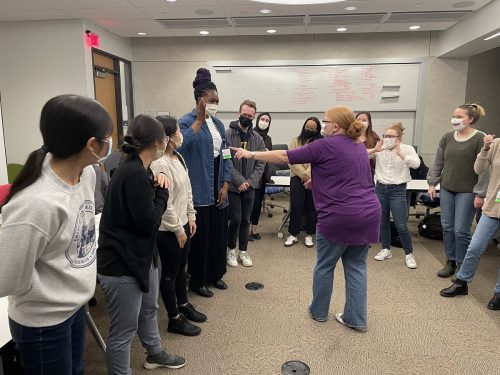

First-year medical students join Kate and Professor Shields for a class picture, posing with the sign for “I LOVE YOU.”

After ten months of planning and countless hours of preparation, the inaugural ASL elective developed into a 10-week course for first-year medical students to learn basic ASL and explore topics of Deaf culture and health inequities. During twice weekly in-person and virtual class sessions, students would leave behind their Anki flashcards and lecture slides to enter a quiet space filled with visual cues and hands-on learning. For many of the students, this class was their first exposure to ASL and Deaf culture and their first meaningful interaction with a Deaf ASL-user as the instructor.

Throughout the course, the students learned hundreds of signs, ranging from numbers and colors to holidays and medical terms. After learning basic ASL fingerspelling, vocabulary and grammar, they eagerly practiced by describing their family trees with neighboring classmates. They soaked in the stories shared by a Deaf Patient Panel and explored effective communication with a certified ASL interpreter. For the final exam, they studied with classmates and flexed their receptive skills on paper. These students took time from their busy schedules to participate in this class, and I am incredibly thankful for their interest and commitment to improving the healthcare experiences of Deaf patients.

Now that the course has come to an end, I’d like to share what I learned along the way. To anyone who hopes to develop a similar elective, here are three factors that are crucial to making it happen: (1) the team, (2) the institutional support and (3) the dedication.

THE TEAM

Our team consisted of six passionate members, including medical students, physicians, ASL interpreters and an instructor who all contributed their unique strengths. Drs. Michael McKee and Philip Zazove from the Deaf Health Clinic provided essential perspectives as ASL-fluent physicians, prominent disability advocates and Deaf individuals. Christa Moran and Leslie Pertz are both medical ASL interpreters with extensive experience bridging the communication gap between patients and providers. Julia Shields, an ASL instructor, brought several years of teaching experience and her lived experiences as a Deaf person. Dr. Alexa Minc, a fourth-year medical student at the time, contributed her institutional knowledge to obtain funding and administrative support. As a first- and second-year medical student, I led the processes of acquiring course approval, interviewing candidates, recruiting students and served as a Teaching Assistant for the elective. Overall, this course would not have been successful without the diversity of perspectives and experiences that each member brought to the team.

THE INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT

In addition to a strong team, the ASL elective benefited from both financial and administrative support from UMMS. To obtain funding, Dr. Minc applied for a Capstone for Impact Grant. Such grants support capstone projects, which are a graduation requirement for all UMMS students. Once approved, this grant provided funding to compensate an ASL instructor for the 10-week elective. Additionally, I received an M1 Summer Impact Accelerator grant to develop and coordinate the ASL elective. Upon course approval, administrators assisted with setting up a Canvas course site and promoting the elective. This support from UMMS was an essential step in hiring an instructor and ensuring the course ran smoothly.

The classroom was filled with smiles as Professor Shields led a game to practice colors in ASL.

THE DEDICATION

From the early brainstorming sessions in January to the last class session in December, each and every person involved showed unwavering dedication to the elective. UMMS faculty and administrators helped to approve and sustain the technical operations. Team members stepped up to interview potential instructors and organize guest presentations. The ASL instructor developed a new curriculum and spent hours driving from Kalamazoo to Ann Arbor for in-person classes. Several students went above and beyond to request additional learning opportunities and expressed interest in a second ASL elective in the spring. These individuals truly embody the “Michigan Difference” that made this elective so special.

So, what’s next for the ASL elective? My team is currently gathering student feedback to improve the course for future participants. This feedback will be central to gaining continued support from UMMS and obtaining consistent funding for an ASL instructor. By popular demand, we plan to offer the ASL elective each fall and develop a spring course that builds on students’ foundational knowledge. In the future, we hope to create educational opportunities for all medical students, faculty and staff at Michigan Medicine, and promote the development of similar electives at other institutions through presentations and publications.

The ASL elective has been a large stepping stone in my journey to improving access to health care for people with disabilities. Planning and implementing this course has made me feel challenged, humbled and supported. Various ASL students have told me that this course was a bright spot in their M1 year, which has warmed my heart tremendously. Most of all, I hope this course ultimately helps these students form unique connections with their future Deaf patients — a form of healing that extends beyond medical treatment.

by Erin Finn | Dec 23, 2021

Some days, even a third cup of coffee won’t do. Despite the intrinsic joys of being a member of a team providing life-altering medical care, medicine is hard. It can leave you tired and stuck in a pattern where days run together and routines become bland. Perhaps coupled with a few too few hours of sleep, not even the glorified stimulant caffeine can do much to add an extra pep in your step.

When I began my core clerkship rotations last year, I found myself in this mind numbing pattern after a few weeks of 5:00 am pre-rounding. I truly was loving being involved in patient care and learning ever-growing amounts of information daily, but something was missing. A newness, a joie de vivre, seemed to have been replaced by the early rounds and the frenetic scramble to pre-op between rounds, a quick breakfast, and the first surgical case of the day.

Stuck spinning my tires yet moving nowhere in this monotony, I realized it was time for change.

Enter scrunchies. On a rare day-off trip to Target with my mom, a pack of bright scrunchies stole my attention. The allure drew me in, despite having arrived at Target with intentions to purchase only a few household items (who hasn’t had this happen at Target, though…), and my money was spent before I even had a chance to consider it.

Early the next morning, pre-pre-rounding, I pulled my hair up into a ponytail and looked over my pack of bright, beaming, joyful, exciting, new scrunchies. I chose a hot pink one, looped it twice around my hair and sensed myself grow a few inches taller. I felt just like my scrunchie looked: bright, beaming, joyful, exciting, and new. No longer was today another day of the ordinary; it was hot pink scrunchie day.

Early the next morning, pre-pre-rounding, I pulled my hair up into a ponytail and looked over my pack of bright, beaming, joyful, exciting, new scrunchies. I chose a hot pink one, looped it twice around my hair and sensed myself grow a few inches taller. I felt just like my scrunchie looked: bright, beaming, joyful, exciting, and new. No longer was today another day of the ordinary; it was hot pink scrunchie day.

Days of the clerkship continued to roll by, each punctuated by a scrunchie. Some days, perhaps days that I was on call and knew would last for many hours or days with feedback from attendings, called for even bolder scrunchies. A friend had sent me cheetah- and zebra-print scrunchies, perfect for when I needed to believe in my own ferocity. A bridesmaid gift from my cousin featured a yellow scrunchie that could be tied into a bow, perfect for when I needed a little more self-confidence. A black scrunchie helped me feel chic and ready to tackle a day in clinic.

Now having completed my core clinical clerkships, I am reflecting back on how my scrunchies have been with me through some of my greatest triumphs, most important lessons, and hardest days of medical school. They’ve been part of relationships with patients and friendships with peers. They’ve added a pep in my step that even a third cup of coffee couldn’t (although perhaps there is some synergy between that third cup and a scrunchie). They’ve helped me re-find my joie de vivre and learn that early morning rounds will never be able to take it away again.

As I approach my upcoming ICU rotation, I look forward to introducing a new pack of scrunchies into the rotation – these ones multicolored and composed of a variety of fabrics, as well as a purple one with a bow – to help mark each new day, accompany me as I learn and grow, support me through the challenging times, and add just a hint more pep with my coffee.

Getting Involved in LEAGUES

Getting Involved in LEAGUES

I genuinely believe that I was fortunate enough to be chosen for these experiences because of the work I previously did to create a

I genuinely believe that I was fortunate enough to be chosen for these experiences because of the work I previously did to create a

Early the next morning, pre-pre-rounding, I pulled my hair up into a ponytail and looked over my pack of bright, beaming, joyful, exciting, new scrunchies. I chose a hot pink one, looped it twice around my hair and sensed myself grow a few inches taller. I felt just like my scrunchie looked: bright, beaming, joyful, exciting, and new. No longer was today another day of the ordinary; it was hot pink scrunchie day.

Early the next morning, pre-pre-rounding, I pulled my hair up into a ponytail and looked over my pack of bright, beaming, joyful, exciting, new scrunchies. I chose a hot pink one, looped it twice around my hair and sensed myself grow a few inches taller. I felt just like my scrunchie looked: bright, beaming, joyful, exciting, and new. No longer was today another day of the ordinary; it was hot pink scrunchie day.