by Sudharsan Srinivasan | Oct 22, 2020

[March 17th – June 8th, 2020: the timeframe during which mandated clinical activities were paused for medical students at the University of Michigan.]

2020 has been quite the year. In these 10 months, our world has been rocked by natural disasters, racial and social injustice, and of course the COVID-19 pandemic. I knew my clinical year of medical school was going to be challenging, but this year has truly provided me with a unique perspective on my patients, learning environment, health, and relationships.

Patients

At Michigan, we undergo seven core clerkships during our Clinical Trunk (second year of medical school). These include Internal Medicine, Psychiatry, Neurology, Family Medicine, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Surgery, and Pediatrics. This was a unique year in that my classmates and I had a roughly three-month pause about mid-way through our core rotations. As I wrapped up my outpatient Neurology clinic on March 17th after receiving an e-mail from our administration that clinical rotations were paused indefinitely, I had no idea when I was going to take my end-of-rotation shelf exam or when I would be back on clinical service. While these questions were eventually sorted out, I had remaining questions on how the patients I had helped care for would fare during a time when physical and social distancing was necessary to preserve health. M1s through M4s were quick to join forces and create M-Response Corps, a student-led initiative to address different on- and off-site patient and community necessities in an organized manner. Examples of student volunteer activities include the No One Dies Alone (NODA) initiative, a Family Medicine Patient Outreach Initiative, a PPE donation center, and a Geriatric Education on Telehealth Access Initiative. As we joined together to provide for patients and community members, it was a beautiful reminder that medicine occurs where we need it to occur.

My attempt in August to smile with a mask and goggles on! Still working on it 🙂

Environment

The Clinical Trunk has us working closely in teams with other students, residents, and faculty. COVID-19 brought many changes to our everyday environments, especially our learning environment. Many of the weekly, in-person lectures we had were transitioned to either a video or online format. For much of June, July, and August, only M2 and M3 students were in the halls of the hospital as our M1s were on an online curriculum and our M4s had just graduated. Even with this drastic change, our faculty worked tirelessly to support our learning on many different levels. From questions about scheduling courses to enabling our class to take end-of-rotation exams remotely, our learning carried on. On return from our brief educational hiatus, our class continued to rotate through the core clerkships with slight augmentations to our schedule. Many of us learned how to conduct virtual patient interviews from a student-led course in May and were able to test our mettle with these newly acquired skills in June and July. While we were away from the hospital, and on our return, our education truly continued without pause. While things will look different in the upcoming months with continued masking, restrictions on personnel count in rooms, and more Zoom meetings, we as students have become adaptable and innovative as we continue to explore new learning opportunities during the Branches (third and fourth years of medical school).

Health

There are so many forms of health and self-care. Given the year 2020 has been, many of us have struggled in one of these departments at one time or another. With COVID resulting in the closure of many business and gyms, I found it more difficult than ever to hit a good workout. I defaulted to running most days during the quarantine-times but also found that it was difficult to not have social interaction with my peers and friends. It was a huge relief to come back to patient care in June as it meant I would also be seeing my friends in-person and having the opportunity to learn from them and with them throughout the remainder of our clinical year. If I’ve learned anything in these past few months it’s that at certain times you need to tell people that they matter, and at other times you need to be told that you matter. Psychosocial health is just as important as physical well-being. In a time when we can feel the most isolated, it is most important to know there are resources to get help and that there are people who will be there for you. So as we all continue to traverse through the remaining 70-odd days of this calendar year, let’s remind ourselves to pause and reflect on how we’re doing, and how those around us are doing. This year, I learned how to care for patients, but I truly also learned how to help myself best thrive in the clinical setting as well.

Relationships

When you’re putting your patients and studying first, it’s sometimes easy to lose sight of everything else around you. With the added twist of not being able to do all the same activities as we could pre-pandemic, it’s pretty easy to lose balance with friends and family. Since returning to the business of clerkship year, I’ve still found the time to go for socially-distanced walks with friends, cook fancy dinners, and spend time with my family. While I did spend most of my waking hours at the hospital these past few months, I have come away with some memorable experiences as well! One of the most memorable rotations I have had is when I finally got the chance to work with my roommate on a Pediatric Cardiology service. Whether it’s spending time studying on a multi-student FaceTime call, catching up with friends who are out-of-state while driving back to Ann Arbor, or taking day trips within Michigan, there are still many enjoyable ways I’ve spent my time building and maintaining relationships this capricious year. It takes quite a bit, but I have found that maintaining a balance between socializing and studying makes the hard times easier and the good times more enjoyable!

As I continue into the Branches portion and the final 18 months of my curriculum, I know I’ll have a lot of clinical knowledge to gain, but I will also fondly remember these past 12 months and the perspective they have provided. While I dive into studying for USMLE Step 1 next week, I know I’ll be working on smiling with my eyes, so that I can be ready to greet my new patients to come this January.

by Noah Mathis & Maria Santos | Oct 8, 2020

I brace myself and walk into my Mr. M’s room. It’s almost 10 a.m., but the lights are off and the blinds are drawn. The air tastes stale. Mr. M has turned his back to the door and is staring intently at the wall. As I ask to listen to his lungs for the fourth time that morning, Mr. M turns his frustration from the wall to me. “You can’t be serious. The resident just listened to my lungs five minutes ago! Why don’t you know what’s wrong with me? I don’t want you waking me up any more.” I apologize and leave the room, telling myself that he is just a difficult patient, that I did my best, that he doesn’t want to see me so I should leave him alone.

The next day, Mr. M’s wife visits and recounts for the team his story. Two years prior, he had been the picture of health. He was upbeat, enjoyed hiking, fishing, and having his family over for barbecues. He had a great sense of humor and had endless stories about good times with his grandkids. But slowly, he began to change. He first lost his energy, then started having difficulty breathing. For two years he had been going from doctor to doctor, trying countless treatments, but still he continued to get more ill. Now, he hardly has the energy to get out of bed, and as doctors tell him his other organs are not working properly, they still cannot tell him why. I realize that the sullen, frustrated man that I have been talking to is entirely different from the person Mr. M’s family sees, and is not how he sees himself.

My experience with Mr. M came halfway through the clinical trunk, the year in the curriculum when UMMS students are introduced to clinical medicine, rotating through a broad variety of specialties. The year is endlessly exciting and full of firsts: the first patient you interview, the first time you suture in the operating room, the first time a patient looks to you for answers, and the first time you connect with patients facing illness and death. For all its excitement, the clinical trunk is also very demanding. The sheer volume of information students are asked to learn, as well as the constant evaluation and feedback from residents and faculty on what needs to improve, can make it difficult to remember why you are there: to learn to take care of others.

We found that the best way to stay in touch with this larger goal was to spend time getting to know our patients. Listening to people tell of their lives outside of the hospital and the things that are important to them, we were able to briefly step away from the duties of learning medicine and re-connect with what brought us to this field to begin with. Hearing Mr. M’s story clarified why he was distrustful toward clinicians and brought to light a side of him that his wife knew well, but we never got to see.

Staffed by Michigan Medicine faculty, residents and students, the VA Ann Arbor Heathcare System is a five-minute drive or bus ride from the main medical campus.

At the end of the clinical trunk, we learned that others had also found the value in patients’ stories of their lives away from healthcare. We were introduced to the My Life, My Story program at the Ann Arbor VA Hospital. Through this program, UMMS students have the opportunity to talk with veterans admitted to the hospital about the important stories in their lives. Veterans can tell about their childhood, their time in the service, their hobbies, families, and memories. Students take what they learn in this conversation and write a short essay, which is added to the patient’s medical record, where the rest of the treatment team can go to learn about their patient as a person.

My Life, My Story is an opportunity for students to reconnect with the values that brought us to medicine. It provides experience in deep listening, empathy, and making sense of stories through the process of writing. We have found it to be a powerful antidote for what can sometimes be a tedious day to day during the clinical trunk, and one of the most personally rewarding aspects of medical school.

The name and details of the patient in this story were changed to make the individual unrecognizable.

by Amy Blasini | Oct 1, 2020

Before even starting medical school, I worried about burn-out and that I would not live up to the type of physician I aspired to be. In an effort to preserve my compassion, I dove into narrative medicine. I carved out time to learn more than people’s maladies by engaging with their stories. I created a list of twenty books to read in the year before I matriculated medical school. From The Empathy Exams to The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, I read for at least an hour each day on my commute to work. During our core clerkships, when I had little time to dedicate to reading, I read patient blogs before going to bed. I followed two blogs in particular, one from Brooke Vittimberga and the other from Julie Yip-Williams. These stories helped me break out of the mindset of constant evaluation as a medical student and gave me perspective, enabling me to become an empathetic, caring human again. It felt (and still feels) urgent to connect to the humanism of medicine.

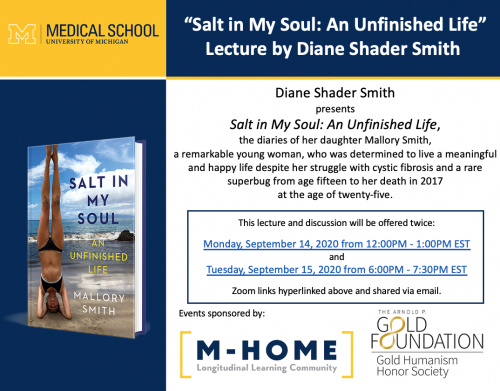

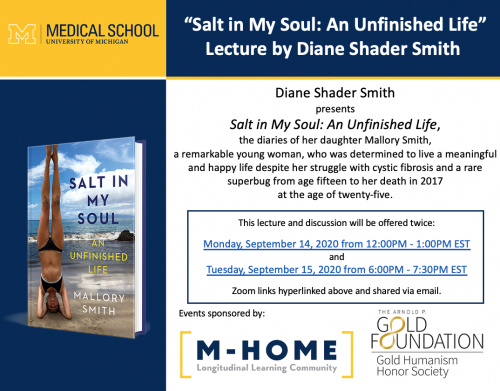

When it came time to choose a Capstone for Impact project, I knew I wanted to focus on the medical humanities, and I had a book in mind. Salt in My Soul: An Unfinished Life by Mallory Smith is a posthumously published memoir of Mallory’s life battling cystic fibrosis. I was lucky enough to know Mallory during our years in college together. After reading her book, I grew to better understand the life of Mallory both as a friend and as a patient with a deep and intimate knowledge of the other side of medicine. Mallory writes about her brave battle with cystic fibrosis but refuses to be defined by the disease. Her prose gives a blueprint for building a fulfilling life while living with a chronic illness, addressing issues around disclosure of an often invisible illness, pain management in light of the opioid epidemic, the power of caregivers on her quality of life, insurance obstacles, mental health, body image, and end-of-life choices. I knew that Mallory’s legacy was a significant contribution to the medical community and to the medical humanities, and I was eager to share her story with our community.

Through the Capstone for Impact funding, we were able to supply 150 copies of Salt in My Soul to interested medical students of all classes and to host the author’s mother, Diane Shader Smith, for two book talks at the medical school, co-sponsored by M-Home Reads and our chapter of the Gold Humanism Honor Society. We had the unique opportunity to hear the perspective of her family, who served as her caregivers for much of her life. As doctors, we engage in just one part of the care that people with chronic diseases receive. Mallory’s book and family opened up opportunities to understand a fuller picture of life with cystic fibrosis. The talk took place during the “Transition to the Clerkships (TTC),” a multiweek course during which second-year medical students prepare to enter the clinical space. Despite the new obstacle of COVID, the book talks were a success, and wouldn’t have been possible without the advocacy of Jen Imsande, PhD, Dr. Barnosky and Kendra Lutes.

Through the Capstone for Impact funding, we were able to supply 150 copies of Salt in My Soul to interested medical students of all classes and to host the author’s mother, Diane Shader Smith, for two book talks at the medical school, co-sponsored by M-Home Reads and our chapter of the Gold Humanism Honor Society. We had the unique opportunity to hear the perspective of her family, who served as her caregivers for much of her life. As doctors, we engage in just one part of the care that people with chronic diseases receive. Mallory’s book and family opened up opportunities to understand a fuller picture of life with cystic fibrosis. The talk took place during the “Transition to the Clerkships (TTC),” a multiweek course during which second-year medical students prepare to enter the clinical space. Despite the new obstacle of COVID, the book talks were a success, and wouldn’t have been possible without the advocacy of Jen Imsande, PhD, Dr. Barnosky and Kendra Lutes.

As I reflect on this event, the culmination of more than a year of planning, I’m reminded of how important it is to center the patient experience in our practice of medicine. Literature is one of my avenues for reconnecting to medical humanism. I am not alone in the venture. The most rewarding part of the Capstone for Impact project was witnessing how students who are about to enter the clinical environment sincerely engaged with the material. Narrative medicine is one way that patients like Mallory can make their impact on generations of medical practitioners. It is up to us to honor their legacy by reading their stories.

Now, as I prepare to start residency next year, I’m crafting a new list – taking any and all book recommendations!

by Reinie Thomas | Sep 17, 2020

You never forget your first, actual patient. The first year at Michigan is spent learning basic science, disease processes, general history-taking and physical exam practice on standardized patients. It feels like a totally different ballgame when you take all these skills and step into a room with a person that has come to the hospital with a real problem and is seeking actual care. If you are like me, this is one of the first of many exhilarating but nerve-wracking moments in your medical career. This is the first time we can participate in what we signed up to do: take care of people. However, for some of us, like myself, that transition of translating all the knowledge and skills we have gained into the patient care we have pictured ourselves delivering for so long, is not as fluid as we would like it to be.

The Clinical Reasoning Elective (CRE) was made for medical students like me, along with so many other students for reasons of their own. This is an elective offered by the medical school that gives first-year students (M1s) an opportunity to enter the clinical space and begin practicing, consolidating and receiving feedback when using these skills on real patients in a low-stakes environment. The students are paired up and assigned to a faculty member, either in the emergency department or internal medicine. Having another M1 enter patient rooms with you takes away some of the initial pressure that comes with some of our first, real, independent patient encounters. It is nice having someone at your exact level of training help fill the gaps for things you might forget.

These now M2s are just five of the 104 first-year students that participated in the 2019-20 Clinical Reasoning Elective during their shifts in the emergency department. L to R: Sonia Iyengar, Brittany Gates, Reinie Thomas (author pre-COVID), Taylor Morgan and Sarah Raven

I had the pleasure of not only participating in the elective, but also serving as one of the two CRE Co-Coordinators for the 2019-20 academic year. As a co-coordinator, I had the opportunity to work directly with the CRE faculty leads, Dr. Will Peterson and Dr. Sarah Tomlinson, help recruit students and faculty to the program, and pair the students with faculty members in their desired specialties. My fellow co-coordinator, Charlie Ferreri M2, is someone who I originally had not known all that well, and now I consider him to be one of my good friends and favorite people at the medical school.

I wanted to join this elective for so many reasons. I am someone who will only speak up in a group if I know 100% that I have the correct answer. When I give presentations, I like them to be well-oiled machines so I can be confident with what I am saying and be prepared for any and every question that may come my way. But I have quickly learned, medicine does not work that way. The process of becoming a doctor involves sticking your neck out there and giving your best guess with the information you have. It involves falling on your face time and time again, until you get it right and eventually end up being able to save someone’s life because of trusting this process. I joined the elective because I am that perfectionist, scared to say a wrong answer, anxious when called to deliver a flawed presentation in a short amount of time, with the thought process that staying silent in the back of the group and ‘soaking it all in’ would be adequate. In my short year at the medical school, I learned those perfectionist habits of mine were restricting me from becoming the best possible physician for my future patients.

My CRE faculty mentor is Dr. Marcia Perry in emergency medicine. I am sure you could ask her, but I went from only wanting to watch other health care providers take histories of patients while I observed, to her throwing me in the fire by myself to take some of the most complicated patient histories. That push was exactly what I needed. The number of times Dr. Perry had to remind me ‘this is a safe space’ and that ‘I was never going to improve if I didn’t fall on my face first’ is astronomical. I went from being terrified to deliver an oral presentation to her because of how many gaps and errors I knew would be there, to wanting to give her presentations so she could point out those gaps so next time…I could do it better than the last. The confidence and personal growth I have seen within myself from just a few shifts in the emergency department has given me just a taste of what I am capable of accomplishing and the mentality I need to maintain as I enter my clinical year.

The Clinical Reasoning Elective was a tool that benefited someone like me beyond measure. From the start of the school year, I could see the clear advantage of sticking your neck out with your best guess at a diagnosis or giving your best shot at an oral presentation for corrections…yet I had never been that person to volunteer or speak up to even give myself the opportunity to receive such valuable feedback. Now, I know that falling flat on your face a time or two and exposing your gaps and weaknesses best prepares you to do what you came here for in the first place: become the absolute best physician that you were always meant to be.

by Claire Garpestad | Sep 10, 2020

Wolverine Street Medicine (WSM) is a catchy title for a student group with an even catchier logo (shout out to the M2s who designed it), but what is it really? What is street medicine and why should we – the future doctors of America – care about it?

Beautiful WSM Logo designed by students!! Our goal with branding is to become a recognizable and consistent entity within the communities we serve.

Having majored in Global Health in college and worked as a case manager at a health care clinic for individuals experiencing homelessness prior to medical school, I arrived at the University of Michigan Medical School knowing I wanted to work with underserved populations. But I wasn’t sure what opportunities would be available to a first-year medical student, and on top of that, I wasn’t sure how best to balance a personal passion with a rigorous medical school curriculum. During my first year of medical school, I had moments when I felt bogged down by schoolwork and really missed the rewarding relationships I built during my time as a case manager. I questioned my decision to leave a job I loved so much, and at times even found myself feeling distant from my “why” behind attending medical school.

The infamous, well-stocked van we work out of on our street runs, with our awesome provider, Dr. Pajewski, front and center!

I first heard about Wolverine Street Medicine toward the end of my first year of medical school. It was a brand-new student group at that time, with a different name, but after my first “street run,” I was immediately hooked. I knew that I had found my people, united by a shared sense of purpose and joy in serving those who need it most. Street Medicine is the practice of providing health care and other social supports directly, by meeting unhoused individuals in their own environment. We practice medicine on street corners, under bridges, outside tents and on park benches, in order to break down barriers to accessing health care, meet people where they are, and provide a full spectrum of care to our neighbors in need. Medical students, regardless of future specialty or career interest, can learn so much from working on a street medicine team, from both the providers and patients alike.

On my first street run, I was especially struck by the community created between the street medicine team and the patients they served. I loved working and conversing with Jim, an outreach nurse who has led street teams for more than 20 years. I valued hearing people’s stories and discussing with them the unique health care needs of people living on the street. I was impressed by the trusting relationships Jim and other team members had built with their patients. I am grateful for the flexibility built into the UMMS curriculum that allowed me to get out of the classroom to be a small part of this incredible team.

Clinical student takes a blood pressure during a street run (with trusty Jim and van in background!)

Since that first run, my involvement with Wolverine Street Medicine has only grown. With this, my resolve that medical school was the right decision for me has strengthened, and I now have a clearer vision for where my future career might take me. I am now an M4 and serving as one of the co-directors of operations for WSM, where I get to hone my leadership skills and practice my clinical skills by spending more time than ever before on street runs. I have gotten to know our regular patients better and begun to build those relationships that so struck me during my early runs. I recently finished a month-long “Health care for the Homeless” elective, which consisted of regular street runs supplemented by online learning. The opportunity to spend a whole month dedicated to this work is a unique aspect of the UMMS Branches curriculum that I have come to greatly value.

I am excited to watch WSM continue to grow this year, and I look forward to many more street runs throughout my final year of medical school. I am even more excited, though, to take what I learned from WSM, Jim, our providers, and most importantly, our patients, with me into my future career as a physician.

To learn more about Wolverine Street Medicine, please visit: https://www.wolverinestreetmedicine.org/

Learn more about our work during the COVID-19 pandemic, visit: https://news.umich.edu/u-m-med-students-support-homeless-shelters-with-critical-supplies/

by Paulina Devlin | Aug 27, 2020

Before I started medical school, I was curious about what students do on a daily basis in the clinical years, and more specifically the Clinical Trunk. I understood I would work with patients and professors, but what does that look like? Now, I know schedules depend on the clinical environment; inpatient services, outpatient clinics, surgical, procedural, and emergency services all run differently. Students experience all of these settings and are part of the medical team in each one. The Clinical Trunk is filled with profound connection and learning from real-life experience from patients, guided by teamwork. In order to help shed some light on the daily responsibilities of a clinical student, I want to share my experiences on a recent Friday of the Pediatrics clerkship.

5:00 am- Good morning! I like to ease into my day, so I eat oatmeal while reading an article in the New York Times. Then I wake up my critical-thinking brain by sipping coffee and watching a video on Sketchy Medical, which is a medical education review program.

5:45 am- Walk to Mott. From my apartment in the White Coat Area, it is a brisk, 10-minute walk to the closest hospital entrance. Once in the hospital complex, I head to C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, passing through different patient care areas, clinical departments, and research facilities.

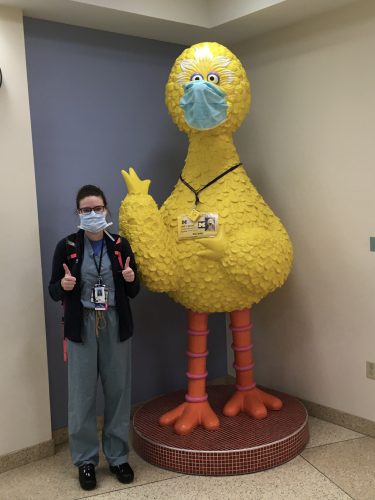

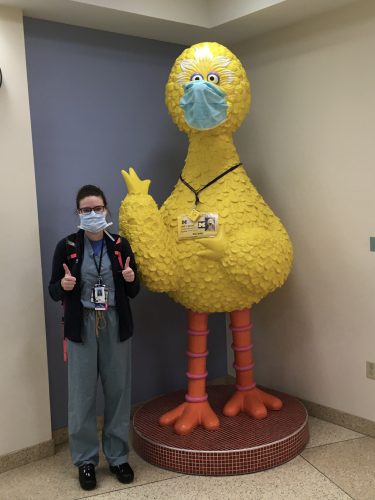

Good morning to Big Bird at one of the entrances to Mott Children’s Hospital.

6:05 am- Arrive to team room and pre-round. I am part of a general Pediatrics team during the inpatient portion of this clerkship. The medical team includes one attending physician, one “senior” resident who is in their second or third year of residency, two interns who are first-year residents, one Branches “sub-intern” who is a medical student who completed the Pediatrics clerkship last year and now has more clinical responsibilities, and two Clinical Trunk med students. The residents and students work together in our team room, our home-base. Spending time in the team room leads to some of the most entertaining moments of clinical year; shared clinical experiences can bring people together.

In the morning, we start by pre-rounding, which means reviewing the patient’s chart for overnight changes, checking in with the overnight team, and walking over to the patient’s room to talk about how they are feeling and to examine them. After gathering all this information, I synthesize my assessment of how the patient is doing and draft a treatment plan for the day. This morning routine is one of the most important learning experiences of the day because I challenge myself make clinical judgments and practice deciding what diagnostic and therapeutic options I would suggest to the patient if I was in the position of the residents and attendings. Next, I review my ideas with the intern and the senior resident. When our plan aligns, I am receiving feedback that my clinical reasoning skills are improving. Often, residents have additional treatment considerations, and I learn from their explanations and update my plan. This learning process is iterative each time the team receives new data about the patient, whether that is a new set of labs or information the patient shares about their values.

8:30 am- Start patient-centered rounds. The rounding team is large and multi-disciplinary, including the medical team, a pharmacist and pharmacy students, a dietitian, a Care Coordinator, and a Resident Assistant. This morning, I have a question about a side effect of my patient’s medication, so as we wait for the team to assemble, I chat with the pharmacist and pharmacy student. Next, in most specialties, students and residents propose the plan to the attending, the team discusses the treatment options outside the patient’s room, and then we enter to discuss with the patient. In Pediatrics, the team enters the patient’s room for family-centered rounds first, and the entire process occurs with the patient and their parents. Family-centered rounds promote shared-decision making, and they are also an excellent challenge for medical students to make sure we explain our thoughts in ways that everyone can understand.

10:30 am- Finished rounds (early today). The team “census,” or number of patients that we are taking care of, happens to be a little less than average. I hope that means kids in the area are safe and healthy! The larger team disperses to work and the medical team heads back to the team room. Now it is time to carry out the plans that we discussed on rounds. I page the Speech Language Pathology team about one of my patients, and they call me back to talk about how they can help. After I finish the discussion and check-in with the intern, I work on my patient’s daily progress note and share it with the residents when I’m done. Our attending physician returns to the team room and spends a half-hour teaching us about a research subject that came up during rounds; the evidence for and against car-seat angle testing before babies are discharged from the hospital.

11:30 am- Lunch break. My Clinical Trunk student partner and I head to the Mott Cafeteria. I bring my lunch and he buys, so we meet outside to eat. We talk about politics and family. My peers have diverse past experiences, and I love learning about their perspectives. After finishing off an afternoon coffee, we head back to work.

12:15 pm- Afternoon work. The intern and I review the progress note that I wrote and then we share it with the attending. Next, I check in with my patients and their families. With one patient, I sit on the floor and play with toy farm animals while I chat with the patient’s mom. We talk about how the patient was initially diagnosed with several conditions at birth, and I learn about her perspective on the patient’s progress. After spending time with this family, I take a walk around the floor with one of the school-age patients and their mom. It feels rewarding to be able to learn more about the patients beyond what I can read in their medical chart.

1:45 pm- Education. Our team carried out our plans for the day, and we await another admission. One of the interns teaches me about common pediatric gastrointestinal concerns. The Speech Language Pathology team that I consulted earlier calls back to discuss their suggestions, and I chat with them and then share their suggestions with the intern.

2:30 pm- Walk home. On Fridays, like today, clinical students have educational lectures, so we leave the clinical world early. If we did not have lectures, I would have stayed until the senior resident sends the students home, usually around 4-5 pm or after we complete an admission.

3:00 pm- Pediatric learning session, Zoom edition. Usually these lectures are conducted in person, but due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we are adapting to Zoom versions. During the first hour, we review pediatric developmental milestones (Do you know how many words a baby should be saying at 18 months?) and then we discuss pediatric rashes.

5:00 pm- Chat, eat, study. Lectures are finished and my roommate arrives home. She is also a Clinical Trunk student, on a different “track” than me, which means her clerkships are in a different order. She’s on Internal Medicine now. I love having a med student roommate; it feels so refreshing to talk and laugh together, and having a friend at home helps me to be socially connected during demanding studying times. After we chat, I heat up leftover spaghetti and study for the Pediatrics shelf exam. The shelf exam is a test that takes place at the end of each clerkship.

7:00 pm- Short running break. I need a study break, so I decide to go on a short run. There are many places to run in Ann Arbor, including my favorite route that winds through the White Coat Area and Island Park. I am not a great runner, but it has been a convenient “high-yield” (a favorite medical student adjective) way to stay active. The last part of my run faces the hospital. I always look up and feel inspired by all the patients, providers, and staff inside at that moment, who are collectively working to help patients go home comfortable and healthy.

A view of C.S. Mott Hospital and University Hospital

7:30 pm- Back to studying. I return to studying practice questions.

9:00 pm- Talking time. I call my significant other via Google Hangouts. Since it’s Friday, I do not have to wake up early the next day, and I look forward to a long chat. He lives and works in California, so we make long-distance work by talking each day. Our calls are a source of support and encouragement during the successes and stresses of medical school. We also visit each other on switch weekends, which are the weekends between different clerkship rotations when I do not have studying obligations. I am so proud that while we work toward our professional goals, our relationship has strengthened.

10:00 pm- Bedtime. Time to catch some rest! I look forward to a Saturday of studying, followed by having dinner with my family in the evening.

During a typical inpatient day, I learn through clinical practice, didactic teaching, and independent study. Some days have more time dedicated to rounds and others have more direct patient care. What remains constant is the opportunity to learn about caring for patients and to work with talented teammates toward a common patient-centered goal. Studying and activities that support my well-being are also personal priorities. Whatever the schedule, bringing an eagerness to learn and an open mind to each encounter allows me to build on what I learn each day to become a caring and thoughtful physician.

Through the Capstone for Impact funding, we were able to supply 150 copies of Salt in My Soul to interested medical students of all classes and to host the author’s mother, Diane Shader Smith, for two book talks at the medical school, co-sponsored by M-Home Reads and our chapter of the Gold Humanism Honor Society. We had the unique opportunity to hear the perspective of her family, who served as her caregivers for much of her life. As doctors, we engage in just one part of the care that people with chronic diseases receive. Mallory’s book and family opened up opportunities to understand a fuller picture of life with cystic fibrosis. The talk took place during the “Transition to the Clerkships (TTC),” a multiweek course during which second-year medical students prepare to enter the clinical space. Despite the new obstacle of COVID, the book talks were a success, and wouldn’t have been possible without the advocacy of Jen Imsande, PhD, Dr. Barnosky and Kendra Lutes.

Through the Capstone for Impact funding, we were able to supply 150 copies of Salt in My Soul to interested medical students of all classes and to host the author’s mother, Diane Shader Smith, for two book talks at the medical school, co-sponsored by M-Home Reads and our chapter of the Gold Humanism Honor Society. We had the unique opportunity to hear the perspective of her family, who served as her caregivers for much of her life. As doctors, we engage in just one part of the care that people with chronic diseases receive. Mallory’s book and family opened up opportunities to understand a fuller picture of life with cystic fibrosis. The talk took place during the “Transition to the Clerkships (TTC),” a multiweek course during which second-year medical students prepare to enter the clinical space. Despite the new obstacle of COVID, the book talks were a success, and wouldn’t have been possible without the advocacy of Jen Imsande, PhD, Dr. Barnosky and Kendra Lutes.