by Jake Rudock | May 25, 2023

Not every path is linear, especially when it comes to going to medical school. Some students may move directly from their undergraduate into M1, others may take a few years off before entering the field. Then there are individuals who have paved their way towards a certain career and turn to medicine as their new goal. My path was somewhere in the middle. With the intention to pursue medicine after my undergraduate degree, a different career delayed my way.

I entered freshman year of undergrad with the intent of going to medical school upon graduation. As an athlete, I balanced sport and academia, knowing they both gave me a unique future opportunity. I completed all required pre-medical prerequisites and graduated in May of 2015 with my undergraduate degree. I transferred to Michigan later that year to continue playing football while working towards a Master’s in Kinesiology. Following my Wolverine season, I was fortunate enough to have the opportunity to keep playing football for another five years after college.

I entered freshman year of undergrad with the intent of going to medical school upon graduation. As an athlete, I balanced sport and academia, knowing they both gave me a unique future opportunity. I completed all required pre-medical prerequisites and graduated in May of 2015 with my undergraduate degree. I transferred to Michigan later that year to continue playing football while working towards a Master’s in Kinesiology. Following my Wolverine season, I was fortunate enough to have the opportunity to keep playing football for another five years after college.

When football seemed to be fading from my future, I poured myself into a year of MCAT prep and working through the application cycle. The goal of pursuing medical school was back at the forefront. I was ready to start living my dream, a full six years from diploma in hand.

Needless to say, I had some anxiety going back to school. On one hand, I knew an MD was exactly where I wanted to be and exactly what I needed to do. On the other hand, I’ve been in meeting rooms and practice fields for the last half decade, a vastly different atmosphere. As I pride myself in being prepared, I desired something that could help get my feet wet, so to speak, before returning to the books full time. I wanted something that could help me adjust between two different worlds.

As fate would have it, a former teammate of mine from Michigan told me about a pre-matriculation program that helped him feel a bit more comfortable before starting the four-year journey of medical school. That program is called LEAD (Leadership and Enrichment for Academic Diversity), a two-week leadership course to aid in the transition of becoming a medical student. Learning more about the program, I realized it would help ready me for the school year. Without hesitation, I sent my application.

Feeling a sense of inferiority as I walked in, it took no time at all to feel welcomed, as if I was part of a team. I gained mentors who were more than willing to help me out with whatever I needed throughout school. Throughout the two weeks, we had various discussions and lessons on what to expect as well as tips and tricks of navigating medical school. While we discussed things you might expect such as study tools and med student resources, we also talked about the emotional journey of medicine, which includes success and failure. I found many of the lessons taken from LEAD helped provide perspective while also gearing me up for the long journey ahead.

Our days were mostly typical of a job schedule, wherein we would get to school around 8:00 and be done around 5:00, give or take depending on the day. Thankfully, no work needed to be completed at home. This scheduling alone allowed me to get back in the groove of things as the previous year I had been focused on waiting for applications to come back, and my wife and I were anxiously awaiting the arrival of our first child. Furthermore, even navigating a simple change of which room and which building we were to meet in proved to be more helpful than I could have initially imagined. According to the coordinator, the change in location that occurred nearly daily was by design.

Our days were mostly typical of a job schedule, wherein we would get to school around 8:00 and be done around 5:00, give or take depending on the day. Thankfully, no work needed to be completed at home. This scheduling alone allowed me to get back in the groove of things as the previous year I had been focused on waiting for applications to come back, and my wife and I were anxiously awaiting the arrival of our first child. Furthermore, even navigating a simple change of which room and which building we were to meet in proved to be more helpful than I could have initially imagined. According to the coordinator, the change in location that occurred nearly daily was by design.

Through LEAD, I was also able to make friends and build a sense of community among my classmates. Meeting periodically throughout the year, we’d learn from someone in the Michigan community about various topics like building your residency application, finding a mentor and creating a CV.

As a bridge connecting my gap years away from academia to the beginning of my medical training, I have no regrets in having devoted two weeks of my time to engage in the LEAD program. The simple step of getting my feet wet provided me with a sense of connectedness and calmness moving forward as I walked across the stage to receive my first white coat.

by Jiwon Park | Apr 21, 2023

Although I can no longer play Liszt etudes or Rachmaninoff piano concertos with the ease that I once had, my deep appreciation for music and piano has continued to be fostered throughout medical school.

On several occasions on the orthopedic surgery residency interview trail, I was asked by faculty, “if you had to choose a career outside of medicine, what would it be?” Without hesitation, I would answer: a concert pianist. In fact, for college, I applied to both music conservatories and normal universities. I won several international piano competitions, made my concerto debut with the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra, performed in recitals at Carnegie Hall, France, and Poland. I ended up attending MIT for college majoring in chemistry, but I continued to study piano at MIT and the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston and performed a concerto with the MIT Symphony Orchestra. After college, I spent a year in Poland on a Fulbright Scholarship doing chemistry research, while also studying Polish classical piano music at the Chopin University of Music in Warsaw.

In medical school, I sought out ways to incorporate music with medicine. The University of Michigan Medical School has a unique program called the Medical Arts Program (MedArt), one of the few programs in the country that connects medical students, residents and faculty to the humanities and the arts. As a first-year medical student, I performed in the Medical Arts Program Artists’ Guild Showcase, which is an opportunity for medical student artists, poets, dancers and musicians to perform at the Kerrytown Concert House in downtown Ann Arbor. I performed Libertango, a piano duet by Astor Piazzola, with a fellow medical school classmate, and Chopin Nocturne Op. 48, No. 1 in C Minor. I enjoyed having the opportunity to perform with my classmates and watch the performances of the numerous, multi-talented medical students at University of Michigan.

In medical school, I sought out ways to incorporate music with medicine. The University of Michigan Medical School has a unique program called the Medical Arts Program (MedArt), one of the few programs in the country that connects medical students, residents and faculty to the humanities and the arts. As a first-year medical student, I performed in the Medical Arts Program Artists’ Guild Showcase, which is an opportunity for medical student artists, poets, dancers and musicians to perform at the Kerrytown Concert House in downtown Ann Arbor. I performed Libertango, a piano duet by Astor Piazzola, with a fellow medical school classmate, and Chopin Nocturne Op. 48, No. 1 in C Minor. I enjoyed having the opportunity to perform with my classmates and watch the performances of the numerous, multi-talented medical students at University of Michigan.

Every year, the Department of Anatomical Sciences at the University of Michigan Medical School, organizes a memorial service to honor donors and their families, and thank them for the gift of knowledge. The ceremony is an opportunity for students, faculty and family to remember the donors through experiences of gratitude. In addition to spoken word, my classmates and I wanted to express our gratefulness to the donors and their families through music. Through coordination with the anatomy faculty, we performed songs on the piano, cello and voice for the 2020 memorial service.

While learning medicine, I also wanted to maintain my piano skills. Practicing piano and studying new piano compositions was therapeutic as I navigated medical school. After spending hours on my computer flipping through Anki flashcards and solving UWorld questions for shelf exams, I would head over to the School of Music’s Earl V. Moore Building to practice piano alongside music students. I loved hearing the kaleidoscope of melodies from various instruments in the hallway as I entered the music building. Through the University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre and Dance (SMTD), U-M students from other departments, including the medical school, are able to take private instrumental and voice lessons from master’s and PhD students in the SMTD. I participated in biweekly, private piano lessons with a student in the SMTD completing her PhD in classical piano performance. During medical school, I studied Debussy Prelude No. 2, Voiles, the 1st movement of Schumann Piano Concerto in A minor, and Rachmaninoff Prelude Op. 3 No. 2. In contrast to being in the operating room, I would sit in front of a piano to focus on perfecting a difficult chord progression, phrasing the theme of a piece with affettuoso, and singing along to a beautiful tune in bass clef.

As a fourth-year medical student, I played the piano in the band for the Smoker, a beloved, annual musical parody of life at the University of Michigan Medical School that is written, directed, produced and performed by medical students. Medical students across all classes come together to sing, dance, act, design, write and perform in the Smoker. The 2023 Smoker was based off of the movie Shrek and titled “VaSHREKtomy.” The band played a wide genre of music, including songs by Smash Mouth, Van Halen and Dr. Dre. Being in the Smoker band was a highlight of my time in medical school (shout out to my bandmates!).

As a fourth-year medical student, I played the piano in the band for the Smoker, a beloved, annual musical parody of life at the University of Michigan Medical School that is written, directed, produced and performed by medical students. Medical students across all classes come together to sing, dance, act, design, write and perform in the Smoker. The 2023 Smoker was based off of the movie Shrek and titled “VaSHREKtomy.” The band played a wide genre of music, including songs by Smash Mouth, Van Halen and Dr. Dre. Being in the Smoker band was a highlight of my time in medical school (shout out to my bandmates!).

While I will be pursuing a career in orthopedic surgery, piano will remain an integral aspect of my life as a therapeutic outlet outside of the hospital and a medium to connect with others through music. I believe that music, like medicine, can bring people together and heal.

While I will be pursuing a career in orthopedic surgery, piano will remain an integral aspect of my life as a therapeutic outlet outside of the hospital and a medium to connect with others through music. I believe that music, like medicine, can bring people together and heal.

by Kelly Beharry | Mar 28, 2023

As the wheels of their plane hit the runway, my parents were greeted with the announcement, “Welcome to JFK International airport.” My mother, five months pregnant at the time, was flying from their then third-world country: Trinidad and Tobago. Like countless other immigrants, my family came under the promise of “the American Dream,” but what does that really look like? For us, it meant the opportunity to access the best education possible.

We settled in the bustling metropolis of New York City, a place that’s home to over 700,000 unauthorized immigrants. Imagine arriving to a foreign country with only a few hundred dollars in your pocket, ineligible for food stamps or Medicaid. You take over-the-counter supplements, daily turmeric and excessive amounts of tea, hoping to stave off any illness. Finding a job becomes a daunting task when you’re suddenly asked to disclose your citizenship status on page eight of the job application. Then, a global pandemic hits, and you’re left jobless without any access to unemployment benefits or stimulus checks. But that’s not all – the mere sound of a police siren or the sight of a law enforcement officer fills you with paralyzing fear. You become accustomed to feeling this way, with a racing heart and sleeping with one eye open becoming a normal part of daily life.

When it comes to discussing the topic of immigration, the mainstream media frequently overlooks a crucial aspect: the 10-year ban that immigrants face if they attempt to visit their home country to see their loved ones. The heartbreaking reality of missing important life events like funerals, weddings and the births of nieces and nephews often goes unmentioned. Yet, despite all these struggles, the opportunity for a better life in America is worth it, and immigrants endure decades of hardship, instability and emotional turmoil to create that better life for their families. This is the story of my parents, two of the many immigrants who came to America.

Medical students, residents, and physicians actively listening to Dr. Jessica Pierce describing how to conduct the psychological evaluation for asylum seekers and refugees.

My journey brought me to the University of Michigan Asylum Collaborative (UMAC), a non-profit, medical student-run human rights clinic. UMAC offers free physical and psychological evaluations to survivors of human rights abuses who are seeking asylum in the United States. As the training coordinator, I recently had the opportunity to invite influential individuals in the field of asylum medicine to present to a room full of medical students, residents and physicians.

One of our speakers was Dr. Vidya Ramanathan, a pediatrician, human rights advocate and medical director of our organization. She trained our attendees on how to conduct the forensic medical exam and write the medical affidavit. Using the Physicians for Human Rights Istanbul Principles, she demonstrated the gold standard of effective investigation and documentation of torture.

Another speaker was Dr. Jessica Pierce, a child and adolescent psychiatrist who is passionate about civil rights and social action. She guided the crowd on how to conscientiously conduct a psychiatric/psychological asylum evaluation. Dr. Pierce defined psychological torture, explained the psychiatric review of systems and challenged us to strengthen our cultural understanding, especially when working with this population.

We closed with Teresa Duhl, the fund development and engagement manager at Freedom House Detroit. She informed us on asylum law through a unique case study following a family’s journey to the United States. Freedom House is a non-profit organization in Detroit devoted to helping asylum seekers rebuild a safe life through providing shelter, community and legal assistance. Many of the cases we receive are referred to us from Freedom House. Our training program is designed to equip our volunteers with the skills needed to provide free forensic medical evaluations to those escaping persecution and seeking refuge in America. After successfully completing the training program, our attendees can volunteer and make a meaningful difference in the lives of those who need it the most.

As medical students, we may not have the power to change immigration laws or provide direct medical care for all who needs it, but I believe that we can still make a meaningful contribution to the lives of immigrants by giving our time, kindness and commitment to learning more about the challenges they face. Recently, I had the privilege of sitting in on an evaluation case as part of UMAC. This experience opened my eyes to the immense transformative power of medicine and helped me understand that the role of a physician goes beyond clinical presentations and medical diagnoses. A physician must truly grasp a person’s life experiences, strengths, traumas and culture to provide the best possible care. This requires building a deep human connection that forms through empathy, understanding and compassion, ultimately leading to the establishment of trust. What I witnessed on that call was the cultivation of hope and strength through storytelling and advocacy. To be trusted by this person to convey their story and experiences in a medical affidavit left me feeling humbled and grateful. It is a privilege to be part of an organization that challenges me to constantly reflect on my privilege and use it to drive change. By advocating for immigrants seeking to rebuild a safe, secure and beautiful life for themselves and their future generations, I have found a sense of purpose that is truly fulfilling.

To me, the power of humanity lies in our ability to form deep connections and support each other through adversity. While we may not be able to solve all the world’s problems, we can make a lasting impact by lifting each other up in times of need. This is a lesson I learned from my parents, who made selfless sacrifices to bring me to this country and instilled in me a passion for uplifting marginalized populations through service and advocacy. UMAC has provided me with a platform to turn that passion into meaningful action. As I reflect on my journey as a first-year medical student at the University of Michigan Medical School, I feel grateful for the opportunity to contribute to a cause that is bigger than myself and to work towards creating a more just and equitable society for all.

by Anuj Patel & Hannah Glick | Mar 15, 2023

As almost-graduated M4s at the University of Michigan Medical School (UMMS) we have had a lot of exposure to the full breadth of the curriculum from the foundational Scientific and Clinical Trunks during our M1 and M2 years all the way up to the broad elective time in the Branches during our M3 and M4 years. We feel so fortunate that we were both able to develop a strong foundation early on and have the time to explore our own areas of interest later in the curriculum. However, as we moved through the curriculum, one area that we hoped to have more exposure to was LGBTQIA+ health.

As is true for many medical schools across the country, coverage of topics relating to LGBTQIA+ health in medical curricula can feel sparse and disjointed. At the time that we both matriculated, UMMS had existing LGBTQIA+ health teaching during a couple of required sessions in the M1 and M3 Doctoring curriculum, as well as through the optional Transgender Health elective that can be taken in the Branches. While these sessions were certainly necessary and beneficial, we felt that a more comprehensive and cohesive course covering foundational and advanced topics relating to LGBTQIA+ patient care would be highly valuable for UMMS students.

In addition to our own personal experiences with the UMMS curriculum, we also participated in a research effort in collaboration with Dr. Dustin Nowaskie, a current faculty member at Keck School of Medicine and Founder and President of OutCare Health. Through this study, we learned that medical students may need as many as 35 hours of curricular education in order to ensure high levels of LGBTQIA+ cultural humility in patient care. Driven by this, we led the effort to create a new course titled “Introduction to LGBTQIA+ Health”.

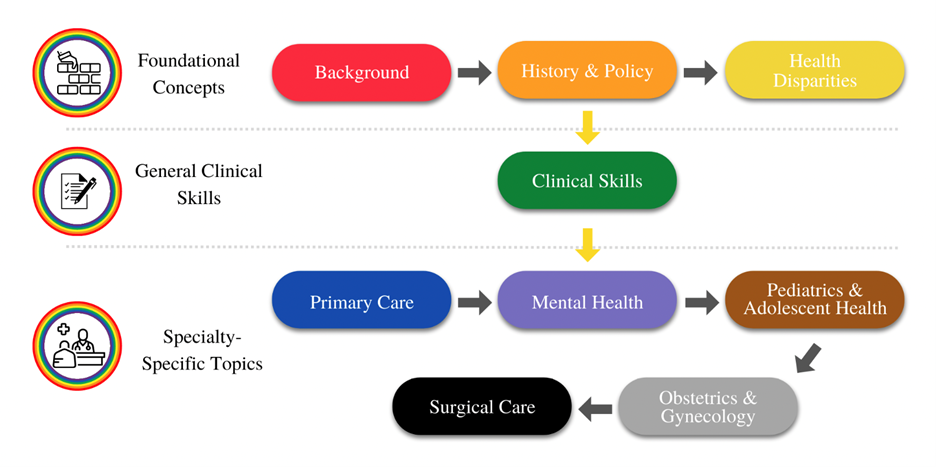

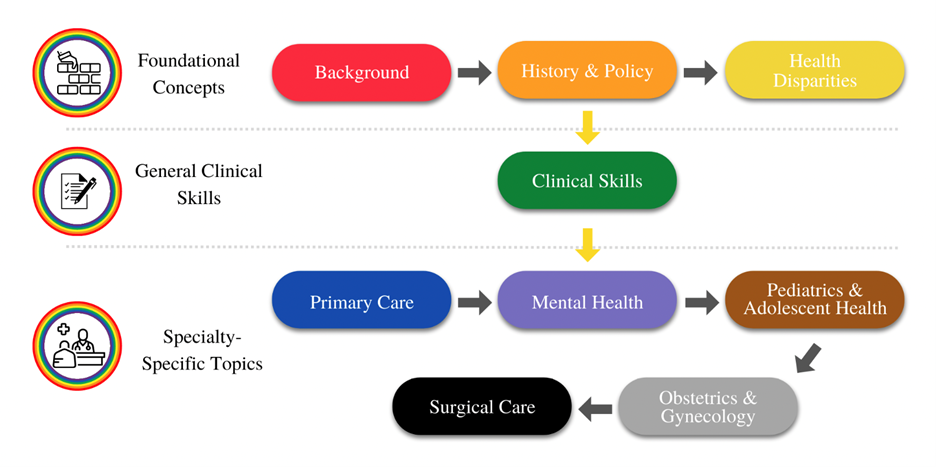

Taking advantage of flexibility in the Branches phase of the curriculum, in addition to the resources available to us via the Capstone for Impact program, we embarked on a nearly one-year journey of developing this novel curriculum. Under the invaluable mentorship of Dr. Julie Blaszczak in the Department of Family Medicine, we brainstormed any and all topics relating to LGBTQIA+ health that a future physician would find useful in caring for a LGBTQIA+-identified patient. Through many weeks of revisions and gathering outside input, we decided that this course would fit best as a two-week, online elective and would cover a broad range of topics in nine distinct modules building from basic, foundational concepts and ending in specialty-specific care topics.

Overview of the nine modules of the course: Starting from basic foundational concepts, moving to general clinical skills, and finishing with relevant LGBTQIA+ care topics in different specialties.

In order to make the course as engaging as possible, we incorporated a variety of learning modalities including required readings, journal articles, podcasts and videos. We also reached out to content experts at our institution and across the country to record lectures, which we embedded into the course. Through OutMD, our LGBTQIA+-focused student group, we also recruited other medical students to help with construction of each of the nine course modules.

After many hours of hard work in planning, designing and building these modules, our team is so proud that this course is up and running for UMMS students to take during their M3 and M4 years in the Branches! From initial data taken from students who have completed the course, we were able to show that students have higher basic knowledge in this area and are more clinically prepared and confident in the care of LGBTQIA+ patients.

We are ecstatic about how this course has turned out, and we hope that it has a lasting positive impact on future UMMS students. More and more people in the U.S. are identifying as LGBTQIA+ and as such we as future physicians have a responsibility to provide the most competent and informed care possible to this growing subset of the population. We hope that this course bridges a gap in medical education and will overall make UMMS graduates more able and comfortable in delivering healthcare to LGBTQIA+ patients.

by Laura Zebib & Sarosh Irani | Mar 2, 2023

Today, only 4.4% of practicing urologists identify as Hispanic/LatinX, 2.4% as Black/African-American and 10.9% as female. These numbers lag far behind the demographics of the urology patient population.

To address the disparity between the urological workforce and the needs of urology patients, there have been great strides to develop mentorship programs within urology. Working in a urology clinic as a medical student, you quickly learn that urology requires creating a safe space in the clinic to discuss topics that can often be stigmatizing such as incontinence and sex. We both got involved in UroVersity leadership during our second year of medical school because of the persistent racial disparities in urological diseases and believe that every patient should have an opportunity to receive care from a provider that they feel comfortable with.

UroVersity is a student-led, multi-level mentorship program that aims to increase diversity, equity and inclusion within the field of urology. This program was created by Dr. Kristian Black, a PGY-3 in the Department of Urology, to address the lack of representation and opportunities for underrepresented groups in urology and other surgical specialties.

Each year, we welcome a handful of students from underrepresented ethnic/racial backgrounds, low-income backgrounds and students who identify as LGBTQ+ to engage in a longitudinal mentorship program. Students are provided with mentorship and guidance starting in their first year of medical school from both faculty and resident mentors and maintain these connections throughout their time here at the University of Michigan Medical School. Through the program, students have an opportunity to explore the field of urology and connect with mentors who can provide them with guidance and support as they navigate medical school and The Match.

In addition, UroVersity provides opportunities for students to gain hands-on experience and exposure to the field. This includes structured shadowing opportunities in the clinic and the operating room prior to starting clerkship year, and a skills-based curriculum so students can excel on their first day of their surgical rotation. These opportunities allow students to develop a deeper understanding of what life as a urologist looks like. UroVersity also works with students and faculty to provide opportunities for research, and several of our second-year students have presented at urological conferences. These experiences allow students to develop relationships within urology while also increasing their competitiveness for the Match.

In addition, UroVersity provides opportunities for students to gain hands-on experience and exposure to the field. This includes structured shadowing opportunities in the clinic and the operating room prior to starting clerkship year, and a skills-based curriculum so students can excel on their first day of their surgical rotation. These opportunities allow students to develop a deeper understanding of what life as a urologist looks like. UroVersity also works with students and faculty to provide opportunities for research, and several of our second-year students have presented at urological conferences. These experiences allow students to develop relationships within urology while also increasing their competitiveness for the Match.

In 2022, UroVersity also worked to increase DEI efforts within the medical education pipeline by working with the Black Undergraduate Medical Association (BUMA). BUMA and UroVersity partnered to set up a surgery open house event, where undergraduate students met with faculty and residents from surgical sub-specialties including urology, ENT and orthopedics. This event helped introduce BUMA students to surgical specialties and dispelled misconceptions that could prevent students from pursuing these careers. UroVersity’s mission is to increase student awareness of the field of urology, and our hope is to continue to provide opportunities for students at both the undergraduate and medical school level.

UroVersity is just one program within the Department of Urology that seeks to improve diversity, equity and inclusion. We are grateful to our mentors and the Department of Urology DEI Task Force for their continued support of our program. Our structured mentorship program, along with the guidance and opportunities that it provides, will help diversify the urology workforce and help our students make informed decisions about their careers. By increasing representation within our field, we hope to bring new perspectives, ideas and solutions to the table to improve patient care and address significant health care disparities.

by Bassel Salka | Feb 2, 2023

I used to frequent the Arb when I was in undergrad at the University of Michigan. I loved the colorful garden, the singing birds and the flowing river. For me, it was the perfect escape from the fast-paced life of student groups, difficult pre-med classes and stressful research. There was one bench in particular that I enjoyed more than any other. Facing the water and surrounded by greenery, this bench was special. By turning one’s head to the left, one can clearly see the large windows of Mott Children’s Hospital towering like a giant over the trees. I distinctly remember looking up at the fascinating building many times wondering to myself if I would ever have the opportunity to work in that hospital as a student. There was nothing I wanted more than to call myself a Michigan medical student.

It is for this reason that, after years of hopeful daydreaming, I was shocked to find myself not entirely at peace when I received the long-awaited acceptance to Michigan Medical School. After a few days of soul searching, I realized the reason for these unexpected emotions. An acceptance to medical school, especially one as esteemed as Michigan, meant that I had to sacrifice some of the activities I enjoyed, I thought to myself. After all, medical school is hard; there is no time for non-professional activities. I resigned myself to the idea that no matter how much I enjoyed planning events for the Arab Student Association, choreographing dance groups for the Arab Xpressions cultural show or leading spring break service trips with the Muslim Student Association in undergrad, there was simply no time for non-medicine-related activities in this new stage in life.

I started M1 year like a “good medical student.” I studied hard for my classes, I worked on research projects and my free time was dedicated to getting some much-needed rest. A few months in, however, I realized that something was missing. My passion for spirituality, community leadership and mentorship were incompletely fulfilled by my current medical school routine. Specifically, by not working with my cultural or religious communities like I had in undergrad, I felt purposeless. After catching up with an old friend studying at a medical school on the East Coast and realizing that he felt similarly, we decided to do something about it.

I started M1 year like a “good medical student.” I studied hard for my classes, I worked on research projects and my free time was dedicated to getting some much-needed rest. A few months in, however, I realized that something was missing. My passion for spirituality, community leadership and mentorship were incompletely fulfilled by my current medical school routine. Specifically, by not working with my cultural or religious communities like I had in undergrad, I felt purposeless. After catching up with an old friend studying at a medical school on the East Coast and realizing that he felt similarly, we decided to do something about it.

Taking advantage of Michigan’s flexible curriculum, my weekends started to consist of long drives and flights to medical schools across the country. From Chicago to DC, I began to meet with Muslim students at other medical schools to learn more about their experiences and discuss the prospect of a faith-based professional development group. By the start my clinical year, conversations had transformed into resume workshops in Detroit, clothing drives in Philadelphia, Ramadan dinners in San Francisco and more. The American Muslim Medical Student Association (AMMSA) was born. By the end of clinical year, AMMSA had grown to over 70 schools and hosted the first-ever national Muslim Medical Conference consisting of more than 300 students in Ann Arbor. A quarter of those attending hailed from communities underrepresented in medicine.

Clinical year is often described as a year solely for studying and time in the hospital. However, for me, it consisted of long meetings, travel to other cities and learning the logistics of maintaining a 501(c)(3). It was difficult: I sacrificed some sleep and time otherwise spent on traditional aspects of career development. In exchange, however, I felt fulfilled. I woke up every morning filled with energy and purpose. I learned how to manage large groups of people and manage time effectively. I even learned the fundamentals of fundraising and large event planning.

Now, approaching my fourth year of medical school and looking back at the AMMSA journey, it is clear that medical school is not a place where passions and interests come to die in exchange for rigid medical education. It is a platform where ideas can become a reality and have real-life impact. If it wasn’t for medical school, I would not have had the opportunity to connect with hundreds of other local leaders striving to improve the health of their communities. I would not have the support of my institution in taking big chances. And I would not have developed a passion for mentorship.

Now, when I go to the Arb and sit on the bench near the river overlooking Mott Children’s Hospital, my perspective is entirely different. Whereas before, it was a gaze of longing and hope of finally reaching the destination of medical school at Michigan, now it is an understanding that medical school at Michigan was never the end destination. It is simply another valued step in the lifelong journey of self-development and service.

I entered freshman year of undergrad with the intent of going to medical school upon graduation. As an athlete, I balanced sport and academia, knowing they both gave me a unique future opportunity. I completed all required pre-medical prerequisites and graduated in May of 2015 with my undergraduate degree. I transferred to Michigan later that year to continue playing football while working towards a Master’s in Kinesiology. Following my Wolverine season, I was fortunate enough to have the opportunity to keep playing football for another five years after college.

I entered freshman year of undergrad with the intent of going to medical school upon graduation. As an athlete, I balanced sport and academia, knowing they both gave me a unique future opportunity. I completed all required pre-medical prerequisites and graduated in May of 2015 with my undergraduate degree. I transferred to Michigan later that year to continue playing football while working towards a Master’s in Kinesiology. Following my Wolverine season, I was fortunate enough to have the opportunity to keep playing football for another five years after college. Our days were mostly typical of a job schedule, wherein we would get to school around 8:00 and be done around 5:00, give or take depending on the day. Thankfully, no work needed to be completed at home. This scheduling alone allowed me to get back in the groove of things as the previous year I had been focused on waiting for applications to come back, and my wife and I were anxiously awaiting the arrival of our first child. Furthermore, even navigating a simple change of which room and which building we were to meet in proved to be more helpful than I could have initially imagined. According to the coordinator, the change in location that occurred nearly daily was by design.

Our days were mostly typical of a job schedule, wherein we would get to school around 8:00 and be done around 5:00, give or take depending on the day. Thankfully, no work needed to be completed at home. This scheduling alone allowed me to get back in the groove of things as the previous year I had been focused on waiting for applications to come back, and my wife and I were anxiously awaiting the arrival of our first child. Furthermore, even navigating a simple change of which room and which building we were to meet in proved to be more helpful than I could have initially imagined. According to the coordinator, the change in location that occurred nearly daily was by design.

In medical school, I sought out ways to incorporate music with medicine. The University of Michigan Medical School has a unique program called the

In medical school, I sought out ways to incorporate music with medicine. The University of Michigan Medical School has a unique program called the  As a fourth-year medical student, I played the piano in the band for the

As a fourth-year medical student, I played the piano in the band for the  While I will be pursuing a career in orthopedic surgery, piano will remain an integral aspect of my life as a therapeutic outlet outside of the hospital and a medium to connect with others through music. I believe that music, like medicine, can bring people together and heal.

While I will be pursuing a career in orthopedic surgery, piano will remain an integral aspect of my life as a therapeutic outlet outside of the hospital and a medium to connect with others through music. I believe that music, like medicine, can bring people together and heal.

In addition, UroVersity provides opportunities for students to gain hands-on experience and exposure to the field. This includes structured shadowing opportunities in the clinic and the operating room prior to starting clerkship year, and a skills-based curriculum so students can excel on their first day of their surgical rotation. These opportunities allow students to develop a deeper understanding of what life as a urologist looks like. UroVersity also works with students and faculty to provide opportunities for research, and several of our second-year students have presented at urological conferences. These experiences allow students to develop relationships within urology while also increasing their competitiveness for the Match.

In addition, UroVersity provides opportunities for students to gain hands-on experience and exposure to the field. This includes structured shadowing opportunities in the clinic and the operating room prior to starting clerkship year, and a skills-based curriculum so students can excel on their first day of their surgical rotation. These opportunities allow students to develop a deeper understanding of what life as a urologist looks like. UroVersity also works with students and faculty to provide opportunities for research, and several of our second-year students have presented at urological conferences. These experiences allow students to develop relationships within urology while also increasing their competitiveness for the Match. I started M1 year like a “good medical student.” I studied hard for my classes, I worked on research projects and my free time was dedicated to getting some much-needed rest. A few months in, however, I realized that something was missing. My passion for spirituality, community leadership and mentorship were incompletely fulfilled by my current medical school routine. Specifically, by not working with my cultural or religious communities like I had in undergrad, I felt purposeless. After catching up with an old friend studying at a medical school on the East Coast and realizing that he felt similarly, we decided to do something about it.

I started M1 year like a “good medical student.” I studied hard for my classes, I worked on research projects and my free time was dedicated to getting some much-needed rest. A few months in, however, I realized that something was missing. My passion for spirituality, community leadership and mentorship were incompletely fulfilled by my current medical school routine. Specifically, by not working with my cultural or religious communities like I had in undergrad, I felt purposeless. After catching up with an old friend studying at a medical school on the East Coast and realizing that he felt similarly, we decided to do something about it.